By Melanie Anne Phillips

Narrative works in the real world as accurately and efficiently as it does in fiction. Not surprising since fictional narrative is nothing more than our attempt to refine and understand how people are driven and how they behave in the real world.

Narrative works in the real world as accurately and efficiently as it does in fiction. Not surprising since fictional narrative is nothing more than our attempt to refine and understand how people are driven and how they behave in the real world.

At a most basic level, one can see real world narratives emerging in the news every day. And, with only a little training, one can not only understand how things are, but even project where they will go from here.

A good example is the current news story that the United States will be pulling out of the Trans Pacific Partnership trade agreement.

What follows is a non-political assessment of the narrative significance of that move, and where it will likely lead.

To understand this analysis, you need only know two tiny concepts out of the entire universe of narrative structure, and these are they:

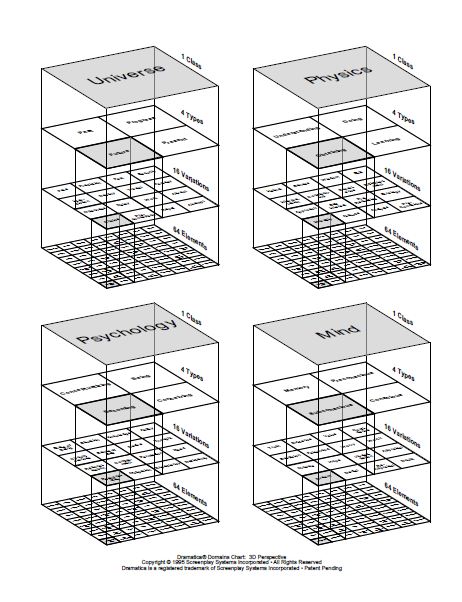

- Narrative is always structured in groups of four dramatic items.

- Of the four, three seem similar in nature and one seems not quite the same.

First, the narrative analysis of the TPP, followed by a more in-depth explanation of these two theory points so you might be better able to apply them to your own real world analyses and your story development as well.

Narrative Analysis of the TPP

There are four world players in the trade agreement narrative:

The EU, the Russian Economic Block, the TPP, and China. As described above, three of these are trade partnerships and one is a single country, which satisfies both of the two theory points listed above.

The quick analysis is that with the United States pulling out of the TPP, there are now five players trying to fit into the world economic quad: The EU, the Russian Block, the TPP (without the USA), China, and the United States.

The projection of where things will go from here is that the three trading partnerships will mostly hold fast (Brexit, notwithstanding), putting the United States and China in direct economic conflict with one another for the four place at the table.

Like a game of musical chairs, the USA and China will seek to push the other into economic decline through currency manipulations, tariffs, and individual deal-making. In order to be economically strong enough to hold its own in this fight, the USA must pull back from its current economic and military commitments overseas. We see this happening already in the stated plans of the current administration in Washington.

In the short run, we will be able to muster the wherewithal to stand toe to toe against China economically, but due to the pull back of United States influence in the world, China will step in to fill that vacuum and gradually form alliances with our allies, increasing their world influence at the expense of ours. But, as they say, that is another narrative.

In short summary, by pulling out of the TPP we are effectively declaring a one-on-one economic war with China in the belief we can triumph on our own, rather than as a group of economically allied nations.

For the long view, here is more about this world economic quad, how and why it came to be, how it functions, and where it will likely go from here:

In our work using narrative analysis for all of the major United States intelligence organizations over the past five years, we learned a bit about the history of how these trade partnerships emerged, which informs this analysis. (Knowing the back story always aids in understanding the current story).

When the old Soviet Union was on the verge of collapse, it recognized it needed to shed many of its component republics, such as Chzechoslovia and the Ukraine. In anticipation of this, it sought western assurances and received promises that the west would not move to exert any political or economic control over these republics.

However, once the Soviet Union dissolved, the Russian Federation discovered that the west was so tempted by the potential power and profits of eastern Europe that, gradually, both political and economic inroads were made.

The EU became the first of the world-size trading partnerships, and its formation clearly threatened the economic and political security of the Russian Federation. In response, the Russian Federation began to sign up its former satellite republics into exclusive mutual trade agreements as part of a new Russian Economic Block.

Each of these became internally unified and emerged as major economic players on the world stage. That left North America, South America and the Pacific Rim as of yet unorganized and trying to go it alone against these large trading partnerships. It also left China on its own as well.

The TPP began as a result of the following reasoning – that China has virtually the same land area as the USA, as well as being almost identical in natural resources, economy, technological capability and trade. They also have more than three times the population of the United States. Further, our outreach through the financial and military support of other nations is a great drain on our economy, whereas the Chinese do not put nearly as much of their GDP into these kinds of endeavors and are growing faster that we are. So, while we are near parity at the moment, the trend is for China to overtake us as the world leader in the next century, if not before.

In order to do economic battle with not only China but the two economic partnerships as well, we organized the TPP to gather all the remaining independent players into a third partnership that would, through its combined strength, be able to hold out against the growing Chinese power for the foreseeable future.

The problem is that in all of these partnerships, the economically stronger nations end up supporting the economically weaker nations in the hope that eventually, all the member nations will rise, even if the stronger nations have to carry the start-up costs for a while. That makes the partnerships unpopular in the stronger nations leading to some defections from the ranks as with Brexit.

This brings us to the current situation – the fore story – in which three trading partnerships are strong enough to claim a place in the quad and do business with each other, while the USA and China do economic battle with each other, weakening them both so that in the long run, each may lose its position or potential position as a world leader with the economic partnerships becoming political partnerships that then determine the destinies of all remaining independent nations.

Naturally, for the independent nations, the most practical solution is to sew the seeds of disruption in the three trading partnerships so that they fracture and eventually fail, leaving both the USA and China as the defacto world leaders, albeit in their weakened condition from the ongoing economic conflict between them.

While these outlooks appear bleak, narrative structure provides much more positive potential outcomes, including win-win scenarios in which all players might prosper. But, as alluded to earlier, that is another story.

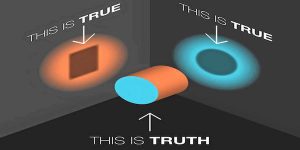

Characters reflect real people in a purified or idealized state. And so, we can see in them qualities and traits that are hard to see within ourselves. One of the most difficult challenges we face every day are exemplified by characters in virtually every story – the inability to confidently understand “what is truth?”

Characters reflect real people in a purified or idealized state. And so, we can see in them qualities and traits that are hard to see within ourselves. One of the most difficult challenges we face every day are exemplified by characters in virtually every story – the inability to confidently understand “what is truth?”

Does your story suffer from “Multiple Personality Disorder”?

Does your story suffer from “Multiple Personality Disorder”?

Narratives are constantly at work in the real world, in business, social movements, and politics.

Narratives are constantly at work in the real world, in business, social movements, and politics. Narrative works in the real world as accurately and efficiently as it does in fiction. Not surprising since fictional narrative is nothing more than our attempt to refine and understand how people are driven and how they behave in the real world.

Narrative works in the real world as accurately and efficiently as it does in fiction. Not surprising since fictional narrative is nothing more than our attempt to refine and understand how people are driven and how they behave in the real world. Even in a chaotic world, the Main Character – be it someone one is talking about or about ourselves as Main Character in our own real world lives – will either be striving to begin something that has not yet started, or to end something that is already going on.

Even in a chaotic world, the Main Character – be it someone one is talking about or about ourselves as Main Character in our own real world lives – will either be striving to begin something that has not yet started, or to end something that is already going on.