Characters reflect real people in a purified or idealized state. And so, we can see in them qualities and traits that are hard to see within ourselves. One of the most difficult challenges we face every day are exemplified by characters in virtually every story – the inability to confidently understand “what is truth?”

In this article, excerpted from the Dramatica Narrative Theory Book I wrote with Chris Huntley, the elusive and changing nature of truth is explored for the benefit of your characters and yourself.

What Is Truth?

We cannot move to resolve a problem until we recognize the problem. Even if we feel the inequity, until we can pinpoint it or understand what creates it, we can neither arrive at an appropriate response or act to nip it at its source.

If we had to evaluate each inequity that we encounter with an absolutely open mind, we could not learn from experience. Even if we had seen the same thing one hundred times before, we would not look to our memories to see what had turned out to be the source or what appropriate measures had been employed. We would be forced to consider every little friction that rubbed us the wrong way as if we have never encountered it. Certainly, this is another form of inefficiency, as “those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

In such a scenario, we would not learn from our mistakes, much less our successes. But is that inefficiency? What if we encounter an exception to the rules we have come to live by? If we rely completely on our life experience, when we encounter a new context in life, our whole paradigm may be inappropriate.

You Idiom!

We all know the truisms, “where there’s smoke, there’s fire,” “guilt by association,” “one bad apple spoils the bunch,” “the only good (fill in the blank) is a dead (fill in the blank).” In each of these cases we assume a different kind of causal relationship than is generally scrutinized in our culture. Each of these phrases asserts that when you see one thing, another thing will either be there also, or will certainly follow. Why do we make these assumptions? Because, in context, they are often true. But as soon as we apply them out of context they are just as likely false.

Associations in Space and Time

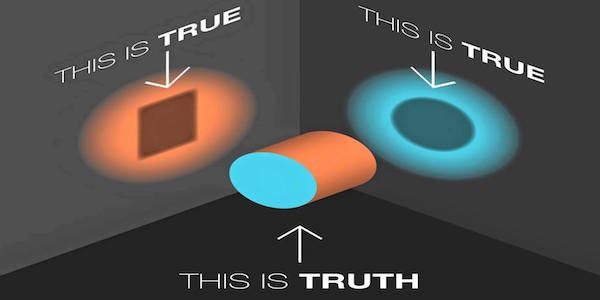

When we see something occur enough times without exception, our mind accepts it as an absolute. After all, we have never seen it fail! This is like saying that every time you put a piece of paper on hot metal it will burn. Fine, but not in a vacuum! You need oxygen as well to create the reaction you anticipate.

In fact, every time we believe THIS leads to THAT or whenever we see THIS, THAT will also be present, we are making assumptions with a flagrant disregard for context. And that is where characters get into trouble. A character makes associations in their backstory. Because of the context in which they gather their experiences, these associations always hold true. But then the situation (context) changes, or they move into new areas in their lives. Suddenly some of these assumptions are absolutely untrue!

Hold on to Your Givens!

Why doesn’t a character (or person) simply give up the old view for the new? There are two reasons why one will hold on to an outmoded, inappropriate understanding of the relationships between things. We’ll outline them one at a time.

First, there is the notion of how many times a character has seen things go one way, compared to the number of times they’ve gone another. If a character builds up years of experience with something being true and then encounters one time it is not true, they will tend to treat that single false time as an exception to the rule. It would take as many false responses as there had been true ones to counter the balance.

Context is a Sneaky Thing

Context is in a constant state of flux. If something has always proven true in all contexts up to this point then one is not conscious of entering a whole new context. Rather, as we move in and out of contexts, a truism that was ALWAYS true may become mostly true, sometimes true, or no longer true at all. It may have an increasing or decreasing frequency of proving true or may tend toward being false for a while, only to tend toward being true again later.

The important thing for your characters is to recognize that they (like us) are just trying to discover what the truth is so they can make the best possible choices for themselves. It is the difference in personal experience that leads to all dramatic (and real world) conflict.

To make your characters more human and to provide them with valid reasons for their actions and perspectives, you need to tell your readers or audience not where each character is coming from, but how they got to that belief system to begin with.

*******

Let me now add a short addendum to this excerpt from the Dramatica Book….

Truth is a process, not a conclusion. If you have ever dipped into Zen, you realize that you cannot fully understand what something is unless you become it, and yet if you do, you lose the awareness of what it is as seen from the outside.

Capital “T” truth is perpetually elusive, as described in the saying, “The Tao that can be spoken is not the Eternal Tao.” Or, in less cryptic terms, if you define something, you have missed the point because nothing stands alone from the rest of the universe and cannot be fully defined apart from it.

The key to open-mindedness and problem solving is to decalcify your mind, to make it limber enough to perceive and explore alternative points of view without immediately abandoning the point of view you currently hold.

That is the nature of stories – when a main character’s belief system is challenged by an influence character who represents an alternative truth. The entire passionate “heart line” of a story exists to examine the relative value of each perspective, and the message of a story is the author’s statement that, based on the author’s own experience or special knowledge, in this particular instance, one view is better than the other for solving this particular problem.

There is no right or wrong inherently. It all depends upon the context, which is never constant. The philosopher David Hume believed that truth was transient: as long as something worked, it was true, and when it failed to work it was no longer true.

And so, the answer to the question posed at the beginning of this article, “What is truth?” can only be “truth is our best understanding of the moment.”

For a tangential topic, you may with to read my article, “The False Narrative,” in which I explore how to recognize, dismantle and/or create false narratives in fiction and in the real world.

And finally, you may wish to support this poor philosopher and teacher of narrative by trying our Dramatica Story Structuring Software risk-free for 90 days, or my StoryWeaver Step By Step Story Development Software, also risk-free.

Problem solving tries to resolve an issue. But if there is an obstacle to a solution, the process of justification tries to find a way around. Sometimes characters get so wrapped up in the attempt to side-step an obstacle that they miss an alternative direct solution.

Problem solving tries to resolve an issue. But if there is an obstacle to a solution, the process of justification tries to find a way around. Sometimes characters get so wrapped up in the attempt to side-step an obstacle that they miss an alternative direct solution.