Every powerful theme pits a “Message Issue” against a “Counterpoint”, such as “Greed vs. Generosity”, or “Holding On To Hope” vs. “Abandoning Hope”.

The Message Issue and Counterpoint define the thematic argument of your story. They play both sides of the moral dilemma. The most important key to a successful thematic argument is never, ever play the message issue and counterpoint together at the same time.

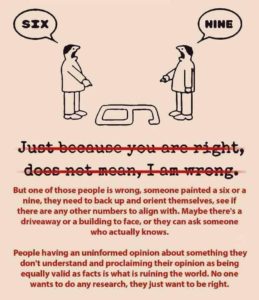

Why? Because the thematic argument is an emotional one, not one of reason. You are trying to sway your reader/audience to adopt your moral view as an author. This will not happen if you keep showing one side of the argument as “good” and the other side as “bad” in direct comparison. Such a thematic argument would seem one-sided, and treat the issues as being black-and-white, rather than gray-scale.

In real life, moral decisions are seldom cut-and-dried. Although we may hold views that are clearly defined, in practice it all comes down to the context of the specific situation. For example, it may be wrong to steal in general. But, it might be proper to steal from the enemy during a war, or from a large market when you baby is starving. In the end, all moral views become a little blurry around the edges when push comes to shove.

Statements of absolutes do not a thematic argument make. Rather, your most powerful message will deal with the lesser of two evils, the greater of two goods, or the degree of goodness or badness of each side of the argument. In fact, there are often situations where both sides of the moral argument are equally good, equally bad, or that both sides are either good nor bad in the particular situation being explored in the story.

The way to create this more powerful, more believable, and more persuasive thematic argument is as follows:

1. Determine in advance whether each side is good, bad, or neutral.

Do this by assigning an arbitrary “value” to both the Message Issue and the Counterpoint. For example, we might choose a scale with +5 being absolutely good, -5 being absolutely bad, and zero being neutral.

If our thematic argument is Greed vs. Generosity, then Greed (our Message Issue) might be a -3, and Generosity (our Counterpoint) might be a -2. This would mean that both Greed and Generosity are both bad (being in the negative) but that Generosity is a little less bad than Greed since Generosity is only a -2 and Greed is a -3.

2. Show the good and bad aspects of both the Message Issue and the Counterpoint.

Make sure the examples of each side of the thematic argument that you have already developed don’t portray either side as being all good or all bad. In fact, even if one side of the argument turns out to be bad in the end, it might be shown as good initially. But over the course of the story, that first impression is changed by seeing that side in other contexts.

3. Have the good and bad aspects “average out” to the thematic conclusion you want.

By putting each side of the thematic argument on a roller coaster of good and bad aspects, it blurs the issues, just as in real life. But the reader/audience will “average out” all of their exposures to each side of the argument and draw their own conclusions at the end of the story.

In this way, the argument will move out of the realm of intellectual consideration and become a viewpoint arrived by feel. And, since you have not only shown both sides, but the good and the bad of each side, your message will be easier to swallow. And finally, since you never directly compared the two sides, the reader/audience will not feel that your message has been shoved down its throat.

—Melanie Anne Phillips

Develop both sides of your theme with

StoryWeaver Software

The message of a story comes from context. It is context that eventually convinces Scrooge that his way of looking at the world is incorrect. Yet, before he was shown the bigger picture, his personal experience presented quite a different picture.

The message of a story comes from context. It is context that eventually convinces Scrooge that his way of looking at the world is incorrect. Yet, before he was shown the bigger picture, his personal experience presented quite a different picture.

There are four throughlines that must be explored in every story for it to feel to readers or audience that the underlying issues have been fully explored and the message fully supported.

There are four throughlines that must be explored in every story for it to feel to readers or audience that the underlying issues have been fully explored and the message fully supported.