In this series of articles, I’m documenting the development of a whole new side of the Dramatica theory of narrative: Story Dynamics.

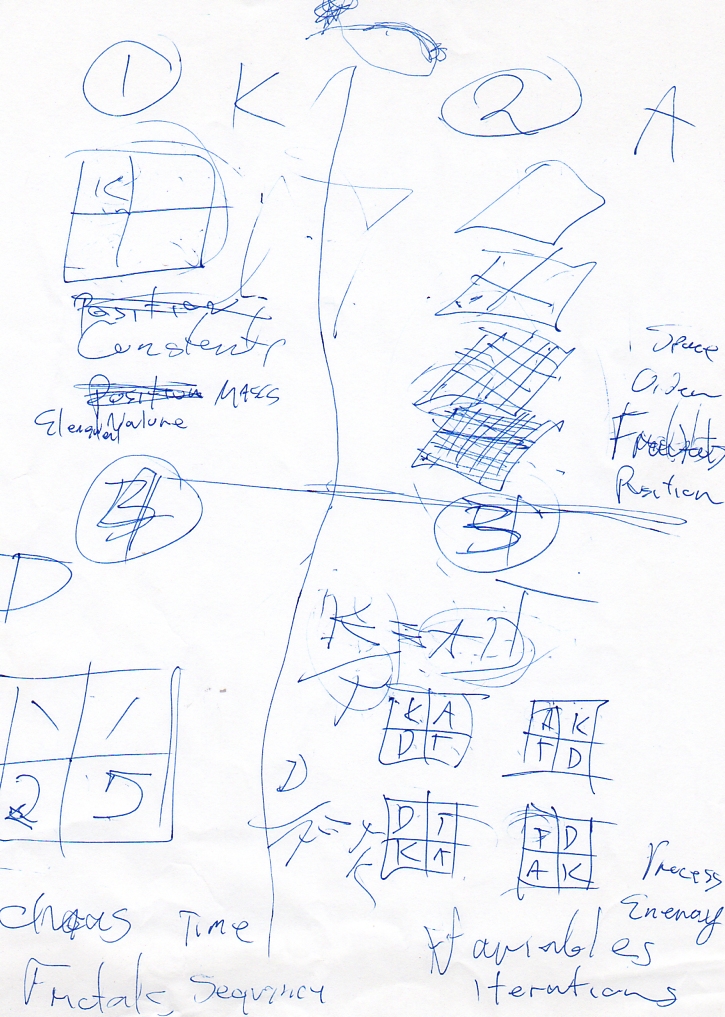

Dramatica is a model of story structure, but unlike any previous model, the structure is flexible like a Rubik’s Cube crossed with a Periodic Table of Story Elements. If you paste a story element name on each face of each little cube that makes up the Rubik’s Cube, you get an idea of how flexible the Dramatica model is.

That’s what sets Dramatica apart from other systems of story development and also what gives it form without formula. Now, imagine that while the elements on each little cube already remain on that cube, they don’t have to stay on the same face. In other words, though there will be an element on each face, which ones it is next to may change, in fact will change from story to story.

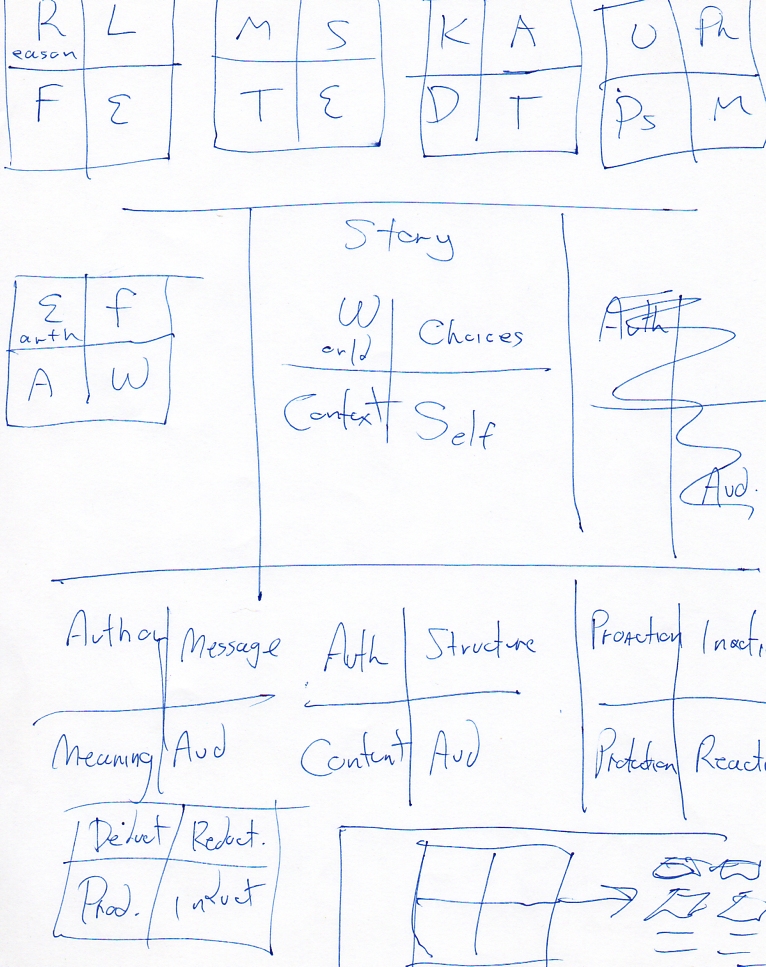

What makes the elements rearrange themselves within the structure? Narrative Dynamics. Think of each story point as a kind of topic that needs to be explored to fully understand the problem or issue at the heart of a story. That’s how an author makes a complete story argument. But, just as in real life, the order in which we explore issues is almost as important as the issues themselves. At the very least, that sequence tells us a lot about the person doing the exploring. In the case of the story, this is most clearly seen in the Main Character. So, the order of exploration of the issues by the Main Character illuminate what is driving him personally.

The Dramatica model already includes a number of dynamics that describe the forces at work in the heart and mind of the Main Character, as well as of the overall story, the character philosophically opposed to the Main Character and of the course of their relationship as well. But, in a structural model – one in which the focus is on the topics and their sequence, there are a lot of dynamics that simply aren’t easily seen.

For example, you might know that in the second act, the Main Character is going to be dealing with issues pertaining to his memories. But how intensely will he focus on that? How long will he linger? Will his interest wane, grow, or remain consistent over the course of his examination of these issues. From a structural point of view, you just can’t tell.

And that is why after all these years I’m developing the dynamic model – to chart, predict and manipulate those “in-between” forces that drive the elements of structure, unseen. Part of that effort is to chart the areas in which dynamics already exist in the current structural projection of the model.

Two of these are Dramatica’s concept of the dramatic circuit coupled with the existing sequential plotting of the order in which issues are explored in every quad of the Dramatica Table of Story Elements.

Beginning with the dramatic circuit, Dramatica divides all the families of elements into groups of four. Why? Simply put, because our minds operate in four dimensions (mass, energy, space and time) our mental systems organize themselves in the same way (knowledge, thought, ability and desire). Now how those internal dimensions reflect or relate to the external ones is thoroughly covered in many other articles. But the point here is that all that we observe and all the processes we use to consider it naturally fall into families of four, which are continually subdividing into smaller families of four, each of which is called a quad.

Now quads have a lot of different aspects and relationships among the elements they contain. For example, each element of a quad will function in one of the following for ways: as a potential, resistance, current, or power. In other words, any functional family into which we might organize what we observe, and any family of mental processes the work together to find solutions or come to understanding will function as a circuit, not just as elements in a bag.

Which element functions as which kind of force is determine by the dynamics that act upon them. Almost amazingly, I can say with some pride, the patented Dramatica Story Engine actually calculates which element is which part of the circuit based on the existing dynamics tracked by the model. But, we’ve suppressed that output ever since Dramatica was first released nearly twenty years ago because it was just SO much information that it confused authors and also because we really didn’t know how to use that information in those days.

The important thing is that the current model can provide this information. And, since Dramatica is a model of the Story Mind (every story has a mind of its own in which the characters are but facets), it accurately reflects the structure and dynamics of our own minds. And so, since the PRCP forces of all the quads taken together form a schematic of the mental circuitry of the mind itself, I decided to call the storyform (map) of each arrangement a psycho-schematic. Pretty clever, huh? But also quite useful!

The PRCP circuits of each storyform describe spatial aspect of a story or of a mind set. But, it does nothing to illuminate the sizes of the potential or resistance or whether that force is increasing, decreasing or holding steady, and for how long. And that is why I’m developing the dynamic model as described in the beginning of this tome.

But, if the PRCP psycho-schematic is the spatial projection of the mind, what about its temporal footprint? That part you can actually see a tip of in the current Dramatica Story Engine: the plot sequence of the signposts.

Signposts are act-resolution appreciations of some of the larger elements in a Dramatica storyform. Each represents sort of an overview topic – an overarching area of exploration that defines the subject matter and principal perspective of each act. There are four signposts, each one being an element in one of the larger quad-families in the model.

Since all four items in a quad must be explored in order to fully understand the issues it covers, the question then becomes in what order will they be explored? Fortunately, we were able to determine a conversion algorithm that became part of the Dramatica Story Engine that takes into account the spatial meaning of how the elements come into conjunction and use that to determine the order in which those elements will come into play.

While the specific are pretty darn complicated, the concept isn’t. Just consider that meaning is not only dependent on what happens but also on the order in which it happens. For example, a slap followed by a scream likely has a completely different meaning than a scream followed by a slap. In the first case, the scream is because the slap hurt. In the second case the slap was to stop the scream. Different order; different meaning.

So, if you can calculate the meaning, which the Dramatica Story Engine can and does, then you can determine the order in which events must have transpired in order to create that meaning. And that is why the plot sequence order is so important to a story making sense. You can cover all the right bases, but if you hit them in the wrong order, the game is lost.

Now when we were first trying to figure out how the sequences were related to meaning, before we wrote the algorithm and built the engine, we started by plotting on our Table of Story Elements the sequence through each quad that we observed in functional stories that seemed to work.

We found that all possible patterns showed up. There might be a circular path around the quad that could start at any element and progress in either direction. There might be a Z or N pattern that zig-zagged through the elements, starting on any and going in either direction. And finally, there might be a hairpin sequence that doubled back over itself in passing through all four elements of a quad.

But predicting which pattern would show up for any given quad, which element it would start on and which direction it would go – well, that drove us crazy. We couldn’t make head or tail of it.

Then, we realized the plotting the sequence on the fixed Table of Story Elements was the problem. We realized that the Table was more like a Rubik’s Cube as I mentioned earlier. And what we discovered was the you could twist and turn the elements within each quad, like wheels within wheels, in such a way that these mixed up patterns all suddenly became straight lines. And when we hit that arrangement of forces, we were able to create the algorithm that describes how outside forces work on a story (or mind) to wind it up, wheel by wheel, creating tension and thereby motivation, and directly tying sequence into the creation and existence of potential, resistance, current and power – how time is related to space.

Yet, here is where we ran into a limit. Though this conversion of meaning into sequence and vice versa turned the model into something of a space-time continuum of the mind, we realized that from this structural perspective we could never calculate how much force or how fast a sequence. And that, again, is why I’m finally breaking down and throwing myself into developing a dynamic model.

Still, a dynamic model, even if fully developed, would also run into the same limit from the other side, and therefore, just as in the uncertainty principle, you could know the structure or you could know the forces, but you could never connect them and know both the structure and the forces at work in it at the same time.

However (and I shudder to think about the other non-story scientific ramifications of this next part), we are beginning to see a means of operating both systems, structural and dynamic, simultaneously and in conjunction (in sync) so that we can observe both at the same time. In other words, if you can’t see the dynamics from the structure nor the structure from the dynamics, then perhaps you can step back and put one eye on each at the same time. Kind of a word-around to the uncertainty principle.

To do this, we first need to find the footprint of the dynamics on the structure, and a few weeks ago my partner, Chris, did just that. He called me up to report that in the shower it had suddenly struck him that the three kinds of patterns we had originally charted on the table actually represented three kinds of waveforms. Essentially, each point on an element is a high or low point in the cycle of a wave. Pretty cool eureka moment!

So, as we often do in considering each other’s breakthrough ideas, I began to ponder whether those three waveforms were sine, square, and sawtooth (which is what they kind of look like) or whether they were the key point in the flow of sine, tangent and secant. Direction through the quad would be indicative of sine or cosine, tangent or cotangent, secant or cosecant. Or, it could determine whether the sine square and sawtooth started at the apex or nadir of their cycle.

Still haven’t made up my mind on that, and I’m half wondering if those two sets of three are really the same thing, just seen a different way. After all, we already know that trig functions show up in many places in the Dramatica theory and model. One place, for example, is that there are three kinds of relationships among the four elements of a quad. The diagonal ones are called dynamic pairs, the horizontal are companion pairs and the vertical are dependent pairs. Dynamic relationships among elements or characters are driven by sine waves, companion by tangents and dependent by secants.

You can understand the functioning of each kind of pair by their names – dynamic relationships are based on conflict, companion based on tangential impact (non-direct influence) and dependent are based on reliance.

Each kind of relationship has a positive and negative version. That’s why there are two of each kind in each quad – one positive and one negative. Positive dynamic pairs conflict but this leads to synthesis and new understanding, Negative dynamic pairs beat each other into the ground and cancel out their potential. Positive companion relationships have good influence upon each other, like friends or, literally, companions. But negative companion relationships create negative fallout on each other, not as a result of direct intent, but just as a byproduct of doing what one does. And finally, positive dependent relationships are “I’m okay, you’re okay, together we’re terrific!” While negative dependent relationships are “I’m nothing without my other half.”

That’s sine, tangent and secant. And the direction or phase of of each wave form determine (and is determined by) whether the relationship is positive or negative within each quad.

But there is one final relationship in a quad that isn’t easily seen. Are the elements of the quad seen as (and functioning as) independent units or are they functioning as a team, a family?

We see this kind of relationship in our ongoing argument about states’ rights. Do we say, “These are the United States” or “This is the United States.” Depending on your view on states’ rights, you’ll gravitate to one or the other.

Another example is when two brothers are always fighting until someone other person threatens one of them, in which case they suddenly bond into a family. As the saying goes, an external enemy tends to unify a population.

So which of the trig functions describes this? Well, since the Dramatica model uses all four dimensions of mass, energy, space and time we rather arrogantly figure that to describe the true relativistic nature of how all four relationships interact we’re going to need something one dimension higher than trig to describe it. Twenty years ago at the height of our hubris we even named this new math quadronometry.

Regardless of what we call it, the effect would be to move imaginary numbers back into the real number plane so that when plotting a sine wave, on a cartesian plane, for example, you would no longer simply go ’round in circles as you continued past 360 degrees to 540 or 720. Rather, additional revolutions would move up the z axis in a helix. In other words, the Dramatica model is neither a sine wave nor a circle. It is more like a “Slinky” toy – seen from the top is is a circle revolving around. Seen from the side stretched out it is a sine wave. But seen from a 3/4 angle you can perceive the actual helical nature of the spiral. One more dimension, but a very important one.

And here is where chris contributed another new understanding to the theory that occurred to him in the same eureka moment in the shower that day. He realized that this fourth kind of relationship in a quad was not about how the two elements in a pair interrelated. Rather, it described how one of the three relationships became (transmuted or evolved) into another. Simply put, how a dynamic relationship could become a companion or dependent one. And in terms of math, how a sine wave could evolve into a tangent or secant.

Well, as you can see there’s not only one footprint of dynamics upon the structure but a whole slew of them – as if a whole herd or army of dynamics was stomping all over the structural ground.

And herein lies the key to connecting the coming dynamic model to the existing structural one. These footprints are like the in interference pattern on a hologram as seen from the structural side. When we develop the dynamic model, the same interference pattern will appear as standing waves with peaks and valleys determined by the interfering forces. The material of the hologram itself, the actual interface, is the space-time environment created in the Dramatica model, and the mind, by its ability to perceive both space and time simultaneously, projects the light of self-awarenss through the interface to observe the resultant virtual image that emerges from the other side.

In this manner, the uncertainty principle is abrogated, at least within the closed system of structural dynamic narratives, and allow use to both fully observe and accurately predict the course of human behavior, in stories and in life.

Melanie Anne Phillips

Co-creator, Dramatica

Learn more about Narrative

Originally published October 10, 2012