Dramatica is a theory of narrative that has a very specific model – rather like the DNA of narrative psychology. But, the model is just the structural linear side of the theory – a way of visualizing how narrative works from a definitive, almost mechanical perspective, like a Rubik’s Cube of story or a Difference Engine of psychology.

But there’s the whole other side of the theory that hasn’t been much expressed – a holistic or analog side that is more attune with the processes and emotions of narrative psychology than the specific nexus points of a given structural storyform.

It’s about time to creative a more balanced view of what Dramatica really is, and how it really works.

So, here’s a concise little crash course on Dramatica from a holistic point of view…

To the heart of the matter, are you familiar with the initial psychological equation of Dramatica that started it all – K/T = AD?

The left side of the equation is all about logic – Knowledge divided by (or parsed) by Thought – K/T. It’s how we reason. But the right side is Ability multiplied by Desire, which created a product we know as Desirability. It is all about motivation or drive – If Ability is zero, motivation is zero. If Desire is zero, motivation is zero. But for any non-zero value of both Ability and Desire, some degree of motivation is created.

When this equation came into my mind for the first time I thought it meant, “One side divides and the other multiplies.” But It turned out it wasn’t a math equation, but a logic equation describing a psychological balance. It reads like this: When Knowledge is divided by (parsed by) Thought, the result is balanced against Desirability.

What is means is that K/T is Knowledge divided by thought or deductive reasoning or, for practical purposes “logic” (or linearity).

In other words, a lot of folks would say, “Emotion does not figure in my logic – my logic is pure reason, critical thinking.” And they’d be right. But, we might apply our logic anywhere, so how did we end up thinking about this particular thing? Desirability.

In other words, logic may be pure, but what we use it on (as opposed to some other topic) is determined by desirability – emotion, holism, touchy-feely.

So, while logic is pure, the application of logic is not. But, that doesn’t put passion at 180 degrees away from logic, because it isn’t against logic, it just directs its use. So, from a passionate or holistic perspective, passion is 90 degrees away from logic, because it also arrives at a conclusion – where to put our logic to work. But, from a linear or reason based perspective, passion is 270 degrees away from logic, because it keeps creeping into the purity.

So, linear thinking says – logic and passion are nothing alike because logic requires evidence and proof and passion does not. But from a holistic way of thinking, logic and passion are quite alike because each arrives at conclusions, and it requires both to direct and then implement logic – they are team members of the greater process.

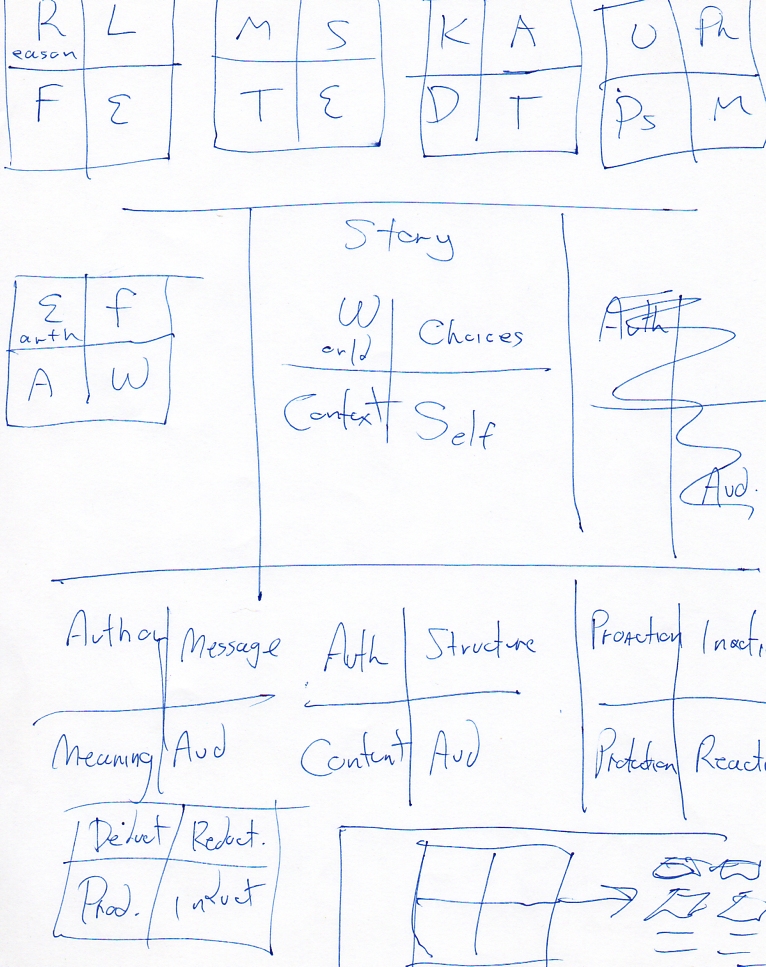

Now this runs right up against the nature of the philosophy of duality. Linear thinking is going to see things as components, separate entities whose borders, perhaps even their natures, can be precisely defined. Things have edges that define them. And this is what K/T is all about – defining things as independent components. And this is how the model of the Dramatica theory was built – in order to best service and communicate with a linear society.

But, the holistic side of the Dramatica theory is more inclusive, rather than exclusive. It focuses on how separate things are actually interconnected, parts of a family or a greater whole.

For a more practical example of this, check out this video clip on my web site about main and influence characters. One of them is going to say, “you and I are both alike” and the other will respond “we are nothing alike.” I’ll tell you why they do this and how it relates to exclusive/inclusive and duality after you see the clip.

Here’s the ink: http://storymind.com/video/examples/you-and-i.mp4

Now that you’ve seen the clip, you can see how often that conversation comes up in stories. And yet we never see it as cliche, because it is the core and essence of that duality problem.

One is saying, “We are nothing alike because I am an apple and you are an orange,” and the other is saying, “No, we are both alike because we are both fruit.”

So, one is using linearity to find the differences that define us as individuals, and the other is using holism to find the similarities that bind us together as a group.

Fact is, each one is right, but each thinks the other is wrong. Why? Because neither can conceive that there is no single answer to the question, “are we alike?” because in some ways we are and in other ways we aren’t.

But why would we have these two perspectives yet never reconcile them? Simply put, life experience shows us that under some conditions, it is better to see things as separate and other times as part of the same group. This is how we determine friend from foe, mine from yours, and even defining ourselves sometimes as individuals and sometimes as part of a family.

Children struggle with this as they grow up, first seeing themselves as part of the family, then trying to find their place within it, then trying to define themselves independently of it. But the truth is that we, like Schrodinger’s Cat, are both independent and dependent at the same time.

That is the core problem in the United States – are we United or are we States? There is no single answer because we are all part of the collective, yet at the same time each state has rights independent of the nation as a whole.

These concepts appear over and over again both in the elements of story structure and in the subject matter we explore in stories because choosing one view over the other is never absolute and must be determined by experience for a given context, yet is always changing, drifting, and what was best seen linearly this week (or in our childhood) may be better seen holistically (as an adult) at this time (though it might change again next week).

Linearity looks to the long-wave truths, calls them predicable, labels them as a law, sets up rules to impose the law, and defines any instance where it doesn’t work as an exception.

Holism looks to the short wave truths, calls them “evolving,” labels them as trends, breaks down barriers to encourage evolution, and defines any instance where change does not occur as an obstacle.

Both are true, neither is right.

In the movie, Kingdom of Heaven about the time of the crusades and the struggle for the control of Jerusalem, the Crusader philosophically asks the leader of the Muslims, “What is Jerusalem worth?” The Muslim leader replies, “Nothing,” turns to walk away, turns back and replies again, “Everything.” And THAT is the truth.

Those who go in search of the answer are already looking in the wrong place, because there is no answer. There are two points of view of equal value conceptually, but different value specifically.

When I was around 5 – before Kindergarten – I was on my swing set on an overcast day with a seamless gray sky. I wondered if I could swing high enough so that nothing but gray would fill my field of vision – no swing set edge, no bushes, no trees – no frame of reference.

I swung higher and higher, and after nearly toppling the swing set, for one brief moment, I saw nothing but gray. And I stopped my swing and sat there and wondered – If there was nothing that existed, would it be black because there was no light or gray because there was no black either?

This was an unsolvable problem. I could see it both ways. But clearly neither was more compelling as being the absolute truth of the matter. In my own childish terms, I realize that there were some questions to which there was not a single all-conclusive answer.

I wasn’t bothered by that so much, but I WAS bothered by the notion that there could be something in existence about which my mind was incapable of finding a single answer. In those days, I was sure the answer existed, I remember thinking, maybe God can see the answer. But if he can, then why is mind mind forever incapable of knowing the answer – in what way is my mind inferior to God’s?

Imagine what kind of five-year-old I was to be thinking such thoughts on my own in the back yard while my mom thought I was just playing on the swing set….

So, the fact that such an answerless question could be asked did not ruffle me, but what stuck in my craw and, in fact, guided everything I explored since – especially my work in developing Dramatica and the Story Mind and Mental Relativity, was to at LEAST find an answer to the question of why my mind is incapable of seeing the answer that surely must exist!

I couldn’t answer THAT question with Dramatica. I couldn’t answer it with 64 years of life-experience. But eventually I did answer it. And then I found peace.

Simply, it isn’t that one side divides and the other multiplies or even one side is exclusive and the other inclusive or even one side defines the differences and the other defines the similarities. No, the way to grok the equation is, one side separates and the other blends.

That blending part is what you don’t see in the dramatica model directly, but it’s affect is omnipresent.

Whenever we abandon our common societal view to step into the shoes of another culture, we discover the same thing – there are those in each society who see the other society as different and those in each society who see the other as the same. But what you don’t often find are those who see the two societies as being both different AND the same.

Embracing that perspective is the closest we can come to becoming one with the Truth.

My advanced work on Dramatica has all been about modeling that. Pretty complex stuff trying to describe something rather simple, but isn’t that always the case?

Now, I don’t expect this note to open your eyes to any new ways of looking at anything or to put peace on your table along with the meat and potatoes, but, like Prince Rupert’s Drop (Google it and watch a video – it’s a cool physics effect), I expect it to disintegrate against against your hard-earned life experiences, at first, and then, by the time you’ve assimilated it for a while, the almost invisible shock wave of this concept will reach the root of the questions you set out to answer, and will work its way back up from your premises to your conclusion, shattering previous perspectives along the way.

But that is not my purpose. Rather, the point for the here and now is to open a door to an additional realm within the Dramatica theory that leads to a more sweeping and more practical appreciation of the model as it initially appears and as you have currently applied it.