First let me define what signposts are in stories and then provide a few hints on how to structure them.

Signposts are the markers that separate one act from another. Think about any well structured story you’ve read or seen on the screen. There are always several points at which you feel that you’ve moved from one act to another, such as in the plot when the characters have finished preparing for a journey and actually embark or in the character arc where the main character finally realizes he has been held back by his best friends good intentions and decides to go solo for the first time.

We intuitively know that a major turning point has been reached and that things will no longer go on as they have and that a whole new direction will reveal itself as the story unfolds.

Now all of that is just felt, but it actually comes from something very solid in story structure: the signpost.

Signposts are like road markers that tell you when you need to turn off the highway you are on and take a side road in order to get to where you’re headed. These signposts are just at the juncture points, yet in between them, you have a lot of ground to cover that is part of your journey.

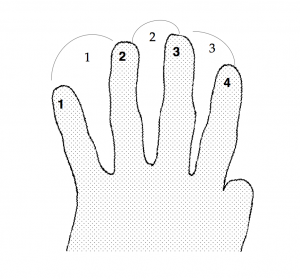

In a standard three-act structure, there are four signposts. To see this more clearly, hold up four fingers on one hand as in the illustration below:

If each finger is a signposts, then you can see three journeys between them.

Readers or audiences feel the journeys because that is the flow of the unfolding of a story over time. But the four fingers define the direction of each of the journeys. So, the first signpost marks the point of departure of the story. The last signpost identifies the destination. the other two signposts in the middle describe the two major turning points in the story when the set up is complete at the end of the first act, and when the climb to the climax begins at the end of the second.

That’s fine conceptually, but how does it play out in actual story development? As it turns out, all four signposts belong a family which is what gives a story a consistent identity as it plays out.

One such family, as an example, consists of the signposts of Learning, Understanding, Doing, and Obtaining. So, in such a structure, the story begins with a general sense that Learning is the undercurrent of what everyone is engaged in. It is the overall background for all that happens. And while not every event or character conjecture has to pertain directly to Learning, there is that feel that establishes that Learning is what the first act is all about.

In practice, the characters in such a story will begin with Learning this or that (the first signpost) and then the act (the first journey) will follow the characters as they learn more and more until they arrive at an Understanding (the second signpost). That’s where we feel an act break as the story changes course from exploring learning to exploring understanding.

In the second act (journey), the characters will progressively grow in their understandings until they are finally able to start Doing (the third signpost). Again, we feel an act break as the internal quest from understanding shifts to the external quest of doing things.

Now the characters do more and bigger things until they are finally able to arrive at their designation, the fourth signpost of Obtaining. End of narrative. End of story.

There are a several families of signposts depending on the kind of story you are telling. And, the signposts don’t always have to be in the same order. In one story, for example, the characters may obtain something that allows them to do something that causes them to learn which leads to an understanding – a complete different order than our first example.

In real storytelling, this second example might be that some kids steal a car (obtaining) and are then able to do (take a road trip across the country), and en route they encounter many people with issues (learning) and eventually arrive home with an understanding about the importance of respecting the property rights of others. Lame, to be sure, but fine as an example of how the signpost order is not locked.

Now as I promised at the beginning, I have now defined what a signpost is. But I still need to explain how to structure them.

To do this, I’m going to share a letter I just wrote to one of my story consulting clients. (Yes, I make my living as a story consultant. Click here to learn more…)

This particular client was taking the precise nature of each signposts way too closely to heart. They were trying to make every single story point in each act tie directly into each signpost, not taking into account that each signpost is just the county you are traveling through and the events in the journey are flavored by that, but not defined by it.

So, here’s the note to my client with some tips for structuring signposts:

Structure should not be applied as rules but as guidelines. Structure gives you the sense of where the meaning is – where the center of the message is.

So in regard to the four signposts, they are like real signposts: they tell you when you have crossed the border from one kind of conjecture to another.

Stories are all about exploration in order to find the narrative because the narrative will provide the understanding of how all the pieces fit together, and therefore what one needs to do to get things to end up in the best possible arrangement.

If a story travels through learning, understanding, doing, and obtaining in that order, it means the story begins with learning. That is the first signpost – the point of departure on their journey. And from there, it starts off on its exploration to learn more and more until it arrives at an understanding (the second signpost). From that point forward, learning is behind and the characters grow more and more in their understanding of what they already learned until they have understood so much that they are finally able to start Doing something about it – the third signpost. From there, learning and understanding are pretty much behind them and their focus is to do more and more until they are finally able to Obtain when they reach the fourth and final signpost: their destination.

As you can see, signposts just mark the dividing lines when the story shifts its focus from one kine of endeavor or outlook to another. You can also think of the four signposts as four rooms in a house. You begin by exploring the first room in which you learn a lot. When you have learned all you can, you move on to the next room where you put all that learning together to arrive at an understanding. When you finally understand all you can, you move on to the next room and begin doing until you have done all you can, and then you move onto the last room to Obtain what you want by taking what you learned, organized into your understanding, turned into the action of doing that results in Obtaining.

Again, in terms of rules vs. guidelines, the signposts give you a general sense of what is going on in each act – what’s the focus or the area of interest. But, that’s not the only thing going on in each act – just the overall background against which everything happens.

Don’t feel that everything that occurs in an act has to somehow connect to the signpost. The signpost is just like the broth in a soup into which all the other stuff is cooked. It gives each act an identifiable flavor but can be filled with all kinds of individual tastes that have nothing to do directly with the flavor of the broth.

Now, looking at your recent work, that is actually WAY too detailed and WAY too focused on each signpost. It is good to have so many opportunities to relate to the signpost – that shows great consistency in your thinking about that act. But, you don’t need nearly a tenth of that many references to the signpost as you have there to convey the overall perspective in that act – you only need enough to clearly establish in the mind of your reader the general background of the kind of exploration that is going on in that act – the kind of activity, interest, or concern.

In other words, don’t try to tie everything that happens in your first act into Learning – that would be forcing the structure and taking structure way too literally. Rather, find as many opportunities as you can in your existing story material for each signpost in each throughline that already is tied into that signpost without forcing it.

W all think in narrative patterns. Our interests are the topics we explore, but we organize the way we appreciate a topic in narrative, which is nothing more than a framework of meaning that ensures we’ve looked at all the meaningful parts of a topic from all the pertinent points of view.

And so, when we write, as with all authors, we automatically organize our story elements into narrative patterns so they make the most meaningful sense. But, we do this by intuition so the perspective is often a bit fuzzy and sometime a little off-true. Structure allows us to focus that already-existing proto-narrative so that each signpost becomes a little more clear as the overall flavor of the background so that all that happens can be seen through that filter before moving on to the next. Like Red, Blue, Green and Brightness, each signpost provides part of the picture through a different filter until we get the full-color version after the last scene at the end.

My advice:

Don’t put so much effort into each signpost. Just find the elements of your story that already point at each signpost and then polish them up a bit so they better reflect it. Let your remaining story elements play against that without trying to force them to direct connect.

Melanie Anne Phillips

Creator StoryWeaver

Co-creator Dramatica