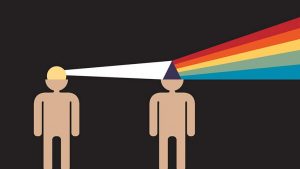

What is an Influence Character? First, let’s look at some wide-ranging examples of Influence Characters in well-known stories to show their use and effect, then a bit about how to put one in your story.

What is an Influence Character? First, let’s look at some wide-ranging examples of Influence Characters in well-known stories to show their use and effect, then a bit about how to put one in your story.

Example 1

In A Christmas Carol, the four ghosts – Past, Present, Future, and Progress (which is Marley, who tells Scrooge about the progress of his growing chain of sins) – share the role of Influence Character, each one taking one fourth of the story to try and change Scrooge, as if they were runners in a relay race.

Without the ghosts the story would just be about Scrooge learning on his own that maybe there’s a better way, but much of the passion of the story and the power of the message would be lost. Message: Do well for yourself, but share some of your good fortune with the less fortunate.

Example 2

In the original Star Wars, the Influence Character is Obi Wan who eventually brings Luke to a point of change and trust in his new-found abilities with the force. In Star Wars, Obi Wan’s Influence is very subtle and gradual and culminates with his disembodied voice saying to Luke just before Luke turns off the targeting computer, “Use the force, Luke. Let go. Trust me…” And Luke is ONLY able to destroy the death star because he turns off the targeting computer and uses his new Jedi skills. Message: We should also trust in our own abilities.

Example 3

In Silence of the Lambs, Hannibal Lecter is the Influence Character who forces Clarice Starling to confront her personal demons (the slaughtering of the spring lambs) that led her to try and save others with a job in law enforcement – “Tell me, Clarice, are the lambs still screaming?” Clarice does not change, cannot let go of her pain “You know I can’t do that doctor Lecter” and so she remains steadfast in her belief system. The Antagonist is not Lecter, but Jamie Gumm – the man who kidnaps the women including the senator’s daughter whom Clarice is trying to save. Message: Let it go, or be forever driven by pain.

Example 4

In The Fugitive with Harrison Ford, Tommy Lee Jones (Federal Marshall Gerard) does not care if his target is guilty or innocent: Kimble: “I didn’t kill my wife!” Gerard: “I don’t care!” But Kimble does care. In fact, he endangers himself and risks his freedom to help others whenever the opportunity presents itself. In the end, it is Kimble’s steadfastness that convinces Gerard that Kimble is innocent. And in the process, Gerard (the Influence Character) is changed. Message: No matter what the risk, don’t give up your compassion.

So, as you can see, without an Influence Character there is no story-long passionate argument regarding which way of seeing the world is the better way, and therefore there is no clear message to the reader or audience.

Now an Influence Character is not necessarily the Antagonist. The Antagonist is trying to prevent the Protagonist from achieving his or her goal. The Influence Character is trying to convince the Main Character to change his or her world view, belief system, or outlook.

Similarly, the Protagonist is not necessarily the Main Character. The Protagonist is trying to achieve the goal. The Main Character is trying to grapple with a personal issue, and is also the character through whose eyes the reader or audience sees the story – in short, we identify with him or her.

Often, the Main Character is the same “person” in a story who is also the Protagonist. In this case, we create a stereotypical hero in which the reader/audience position is with the same character who is leading the charge to achieve the goal.

There is nothing wrong with that combination, but it is like always making the story about the quarterback in a game of football but never telling the story of one of the linemen or the water boy or the coach or the quarterback’s wife. So, if you want a typical hero, make your Protagonist also your Main Character. But if you want to tell a story where the Main Character is allowing us to look at the Protagonist from the outside and to observe him, then you end up with a story like To Kill A Mockingbird in which Atticus is the Protagonist trying to defend the black man wrongly accused of rape in a 1930s town in the South but the Main Character is his young daughter Scout, who gives us a child’s-eye view of prejudice.

Again similarly, the Antagonist is sometimes also given the role of Influence Character, but if you also have a hero who is both Protagonist and Main Character, that can be dangerous because then the opposition to the hero’s goal efforts is the same person who is opposing the hero’s personal belief system. You can do it, but if you have a hero and villain doing both jobs between them, the logistic conflict can easily get mixed up with the moral argument in the minds of the readers or audience. And worse, as an author, you can get so wrapped up in the combined passionate lines between these two characters that you don’t fully connect the dots on either argument, leaving gaps that will be seen (or at least felt by your readers or audience. If those gaps aren’t filled, you essentially have a melodrama in which you don’t make either argument completely yet profess your message at the end as if you did.

Often, authors avoid this problem by creating a dramatic triangle in which one of those two stereotypes (hero and villain) is split into the two parts and the other one remains combined.

For example, in the movie, Witness, with Harrison Ford, he plays the Protagonist – a cop trying to protect the only witness to a murder: the young son of an Amish Woman, played by Kelly McGillis, who is the Main Character: we see the story through her eyes, and through her eyes we observe Ford and consider leaving the Amish to go with him into the world of the “English.” Ford, therefore, is the Influence character as well as the Protagonist, as it is his influence that draws her to a point of decision about leaving. But, the Antagonist is Ford’s Character’s boss on the force, as he is the actual murderer.

And so, a dramatic triangle is created by making Ford both Protagonist and Influence Character with the other two points of the triangle being the Main Character of Kelly McGillis, and the Antagonist of his boss. Fairly complex, it is, and yet it is also compelling and far from cliche, though still perfectly sound. And the message is made: Sometimes it is better to stay in the safety of your extended family than to leave to explore the larger world.

The point being, without an influence character your story will lose the entire passionate argument leading up to the point of choice in which your story’s message should be made, but won’t be.

So how do you add an Influence character and message to your story? Here are a few quick steps:

1. Make a list of all your characters

2. Write a one sentence description of how each characters beliefs or philosophy of life is in conflict with the Main Character’s view of the same thing.

3. All of these different conflicts can be explored in your story, but one needs to be the central issue that will form your story’s overall message. So, consider each, then pick one to be the primary philosophic of conflict of your story.

4. Select the character who is in primary philosophic conflict with your Main Character as your Influence Character.

5. Find as many places in your plot as you can smoothly bring your Main and Influence Characters into conflict over their opposed philosophies, whether it be as advice from one to the other, as an argument, or just by example – having the Main Character see the Influence Character act in a different manner than he or she would in that situation.

6. Over the course of your story, bring your Main Character to a point where he or she must choose either to stick by their guns and hold to their original outlook, believing that their troubles will be resolved if they just remain steadfast long enough, or choose the Influence Character’s alternative view, believing that it holds a better chance to resolve the Main Character’s personal issue.

7. In the end, your Main Character may grow in their resolve to remain steadfast or grow to a point of change. But regardless of how they go, their choice may be right or wrong for resolving their personal issue. This provides you with many ways to prove your message:

Change is good, Change is bad, Steadfast is Good, Steadfast is Bad. Any of these are legitimate; it just depends on the flavor of the message you are trying to send.

8. Don’t forget that if your Main Character Changes, your Influence Character will remain Steadfast, and vice versa. The idea is that one philosophy will trump the other so that both character will, in the end, share the same philosophy. And then you show your readers or audience if that’s was the right choice by showing how it all turns out at a personal level.

9. Keep in mind that whether or not the goal is achieved in a story has no bearing on whether of not the Main Character resolves his or her personal issue. So, you can have a happy ending in which success is matched with happiness, a tragedy in which failure is matched with personal anguish, or a bitter-sweet ending in which success is achieved but with personal anguish or failure is the result of the effort to achieve the goal but with the Main Character finding peace or joy in the end.

10. Think of the passionate “argument” between the Main and Influence Characters about beliefs or philosophies as just as important and requiring just as many pages as the logistic “argument” of the plot about the best way to solve the situational problem of the story.

Now that you know a little more about the Influence Character and its function, hopefully you find a way to include one, as well as the passionate argument, in every story you tell. For if you do, your stories will have heartlines as well as headines, and your readers or audience will be moved as well as entertained.