As a reminder, our step by step approach is all about looking at the needs of the author rather than the needs of the story. From this perspective, we can see four stages in the creative process: Inspiration, Development, Exposition, and Storytelling.

Currently, we are at the beginning of the Inspiration stage in which you have previously jotted down all the creative notions you may already have for your story in Step 2.

In Step 3, we described methods for boiling your initial story concepts down into a log line: a single sentence that expresses the essence of what your story is about.

In this step, we’ll use your log line as a creative core in a method that will generate an expanding sphere of new ideas for your story.

The Creativity Two-Step

The concept behind this method of finding inspiration is quite simple, really: It is easier to come up with many ideas than it is to come up with one idea.

Now that may sound counter-intuitive, but consider this… When you are working on a particular story and you run into a specific structural problem, you are looking for a creative inspiration in a very narrow area. But creativity isn’t something you can control like a power tool or channel onto a task. Rather, it is random, and applies itself to whatever it wants.

Yet creative inspiration is always running at full tilt within us, coming up with new ideas, thinking new thoughts – just not the thoughts we are looking for. So if we sit and wait for the Muse to shine its light on the exact structural problem we’re stuck on, it might be days before lightning strikes that very spot.

Fortunately, we can trick Creativity into working on our problem by making it think it is being random. As an example, consider this log line for a story: A Marshall in an Old West border town struggles with a cutthroat gang that is bleeding the town dry.

Step One: Asking Questions

Now if you had the assignment to sit down and turn this into a full-blown, interesting, one-of-a-kind story, you might be a bit stuck for what to do next. So, try this. First ask some questions:

1. How old is the Marshall?

2. How much experience does he have?

3. Is he a good shot?

4. How many men has he killed (if any)

5. How many people are in the gang?

6. Does it have a single leader?

7. Is the gang tight-knit?

8. What are they taking from the town?

9. How long have they been doing this?

You could probably go on and on and easily come up with a hundred questions based on that single log line. It might not seem at first that this will help you expand your story, but look at what’s really happened. You have tricked your Muse into coming up with a detailed list of what needs to be developed! And it didn’t even hurt. In fact, it was actually fun.

Step Two: Answering Questions

But that’s just the first step. Next, take each of these questions and come up with as many different answers as you can think of. Let your Muse run wild through your mind. You’ll probably find you get some ordinary answers and some really outlandish ones, but you’ll absolutely get a load of them!

a) How old is the Marshall?

a. 28

b. 56

c. 86

d. 17

e. 07

f. 35

Some of these potential ages are ridiculous – or are they? Every ordinary story based on such a log line would have the Marshall be 28 or 35. Just another dull story, grinding through the mill.

Step One Revisited

But what if your Marshall was 86 or 7 years old? Let’s switch back to Step One and ask some questions about his age.

For example:

c. 86

1. How would an 86 year old become a Marshall?

2. Can he still see okay?

3. What physical maladies plague him?

4. Is he married?

5. What kind of gun does he use?

6. Does he have the respect of the town?

And on and on…

Return to Step Two

As you might expect, now we switch back to Step Two again and answer each question as many different ways as you can.

Example:

5. What kind of gun does he use?

a) He uses an ancient musket, can barely lift it, but is a crack shot and miraculously hits whatever he aims at.

b) He uses an ancient musket and can’t hit the broad side of a barn. But somehow, his oddball shots ricochet off so many things, he gets the job done anyway, just not as he planned.

c) He uses a Gattling gun attached to his walker.

d) He doesn’t use a gun at all. In 63 years with the Texas Rangers, he never needed one and doesn’t need one now.

e) He uses a sawed off shotgun, but needs his deputy to pull the trigger for him as he aims.

f) He uses a whip.

g) He uses a knife, but can’t throw it past 5 feet anymore.

And on and on again…

Methinks you begin to get the idea. First you ask questions, which trick the Muse into finding fault with your work – an easy thing to do that your Creative Spirit already does on its own – often to your dismay.

Next, you turn the Muse loose to come up with as many answers for each question as you possibly can.

Then, you switch back to question mode and ask as many as you can about each of your answers.

And then you come up with as many answers as possible for those questions.

You can carry this process out for as many generations as you like, but the bulk of story material you develop will grow so quickly, you’ll likely not want to go much further than we went in our example.

Imagine, if you just asked 10 questions about the original log line and responded to each of them with 10 potential answers, you’d have 100 story points to consider.

Then, if you went as far as we just did for each one, you’d ask 10 questions of each answer and end up with 1,000 potential story points. And the final step of 10 answers for each of these would yield 10,000 story points!

Now in the real world, you probably won’t bother answering each question – just those that intrigue you. And, you won’t trouble yourself to ask questions about every answer – just the ones that suggest they have more development to offer and seem to lead in a direction you might like to go with your story.

The key point is that rather than staring at a blank page trying to find that one structural solution that will fill a gap or connect two points, use the Creativity Two-Step to trick your Muse into spewing out the wealth of ideas it naturally wants to provide.

Your goal for this step, then, is to apply the Creativity Two-Step to your original log line and follow your Muse as far as she can take you. More than likely, you’ll end up with something of a mess – a disorganized mash-up of a huge number of story ideas of many different kinds for your novel.

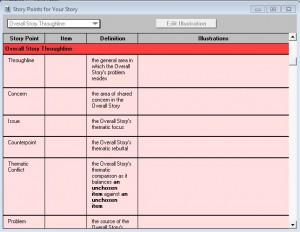

In step 5, we’ll delve into the treasure trove of ideas you’ve generated and begin the process of organizing them into Characters, Plot, Theme, and Genre elements to be further expanded before we move into the Development stage.

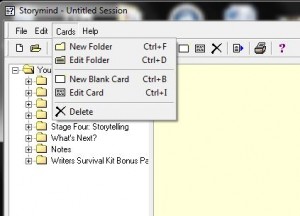

This article was based on our StoryWeaver Step-by-Step Story Development Software that guides you through more than 200 interactive Story Cards from concept to completion of your novel or screenplay. Just $29.95 for Windows or Macintosh.

This article was based on our StoryWeaver Step-by-Step Story Development Software that guides you through more than 200 interactive Story Cards from concept to completion of your novel or screenplay. Just $29.95 for Windows or Macintosh.

Click here for details, demo download or to purchase.