A story begins when the Main Character is stuck up in the highest level of justification. Nobody gets there because they are stupid or mean. They get there because their unique life experience has brought them repeated exposures to what appear to be real connections between things like, “One bad apple spoils the bunch” or “Where there’s smoke , there’s fire.”

A story begins when the Main Character is stuck up in the highest level of justification. Nobody gets there because they are stupid or mean. They get there because their unique life experience has brought them repeated exposures to what appear to be real connections between things like, “One bad apple spoils the bunch” or “Where there’s smoke , there’s fire.”

These connections, such things as – that one needs to adopt a certain attitude to succeed or that a certain kind of person is always lazy or dishonest – these things are not necessarily universally true, but may have been universally true in the Main Character’s personal experience.

This is how we all build up our personalities. We all share the same basic psychology but how it gets “wound up” by experience determines how we see the world. Eventually we reach a point where we’ve had enough experience to arrive at a conclusion that things are always “that way” and to stop considering the issue. And that is how everything from “winning drive” to “prejudice” is formed – not by ill intents or a dull mind but by the fact that no two life experiences are the same.

The conclusions we come to, based on our justifications, free out minds to not have to reconsider every connection we see. If we had to, we’d become bogged down in endlessly reconsidering everything, and that just isn’t a good survival trait if you have to make a quick decision for fight or flight.

So, we come to certain justifications and build upon those with others until we have established a series of mental dependencies and assumptions that runs so deep we can no longer see the bottom of it. This becomes the framework of our thoughts and the template for our behavior.

But what if the situation has changed in some fundamental way so that the entire pyramid of givens we have subconsciously assembled over a period of years is built on a false assumption – the one brick at the bottom that makes all our higher level beliefs and conclusions flawed?

Simply put, we can’t see it. And therefore we cannot help but assume that the problem lies with the situation or with the people involved in that situation, and not with our own point of view.

Stories begin at that moment – when the Main Character’s long-held subconscious belief system, world view, philosophy, or template for behavior comes into conflict with the world around him or her. And the story’s structure is all about how an Influence Character repeatedly brings this conflict to the surface in one context after another until there is so much evidence that the Main Character’s view is incorrect, that he or she must make a choice in a leap of faith: Do I stick with my long-held beliefs, even though they don’t seem to be solving the problem, or do I switch to a new point of view that seems to explain things, yet has never been tried?

Circumstances in the plot force the Main Character to make a choice, or his or her deliberation might go on forever because the evidence is perfectly balanced on each side of this thematic message argument. But in the real world, we are seldom confined in such a way and tend to perpetuate our points of view in the hope that things will eventually work out without having to undo our dearly held beliefs.

And that’s why psychotherapy takes twenty years for us to arrive at the point a Main Character can reach in a two-hour movie or a two hundred-page book.

Some novice writers become so wrapped up in interesting events and bits of action that they forget to have a central unifying goal that gives purpose to all the other events that take place. This creates a plot without a core.

Some novice writers become so wrapped up in interesting events and bits of action that they forget to have a central unifying goal that gives purpose to all the other events that take place. This creates a plot without a core.

A story begins when the Main Character is stuck up in the highest level of justification. Nobody gets there because they are stupid or mean. They get there because their unique life experience has brought them repeated exposures to what appear to be real connections between things like, “One bad apple spoils the bunch” or “Where there’s smoke , there’s fire.”

A story begins when the Main Character is stuck up in the highest level of justification. Nobody gets there because they are stupid or mean. They get there because their unique life experience has brought them repeated exposures to what appear to be real connections between things like, “One bad apple spoils the bunch” or “Where there’s smoke , there’s fire.” The primary colors enable you to create the whole range of shading and tonalities you are trying to achieve in a picture.

The primary colors enable you to create the whole range of shading and tonalities you are trying to achieve in a picture.

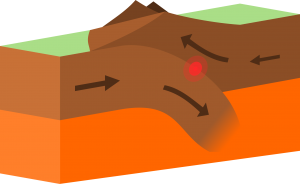

Think of the large structural elements in a story as tectonic plates in geology that push against each other driven by an underlying force. In geology that force is generated by currents in the mantle. In stories, that force is create by the wound-up justifications of the main character that puts him or her in conflict with their world at the point the story begins.

Think of the large structural elements in a story as tectonic plates in geology that push against each other driven by an underlying force. In geology that force is generated by currents in the mantle. In stories, that force is create by the wound-up justifications of the main character that puts him or her in conflict with their world at the point the story begins.