Both Dramatica Pro (Windows) and Dramatica Story Expert (Mac) are geared toward diving right into your story’s structure and making structural choices. But for more intuitive writers this can cause major problems.

Both Dramatica Pro (Windows) and Dramatica Story Expert (Mac) are geared toward diving right into your story’s structure and making structural choices. But for more intuitive writers this can cause major problems.

While Dramatica Pro has a “Start Here” button on the opening screen and Story Expert has a “New User” section in the opening splash screen options, DON’T GO THERE!!!

Each of these puts you directly onto a path to build your story’s structure by answering a series of questions about your story and your intent as an author and that can scuttle your story development efforts right out of the gate.

This existing approach was intended to show the power and usefulness of the interactive patented Story Engine at the heart of both programs. But an unfortunate side effect is that it also makes Dramatica appear to be incredibly complex and unfamiliar, and also requires an steep learning curve before you get comfortable with the system.

What’s more, when questions are asked such as “What is your Main Character’s Domain?” or “What is the Relationship Throughline’s Catalyst?” it is almost sure to frustrate many authors who are excited by their subject matter and ideas and just want to get started developing and improving their stories.

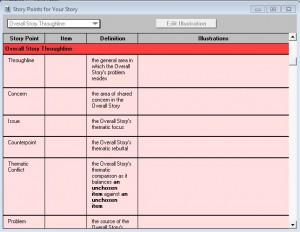

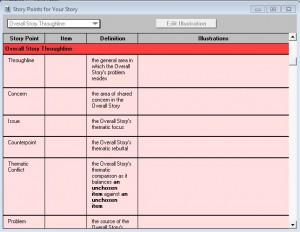

Fortunately, there is a better place to start: the Story Points Window. The Story Points Window lists all the structural elements in your story with a space to illustrate how that element will appear or come into play in your story. This ensures that there are no structural holes caused by forgetting to include an important point.

Fortunately, there is a better place to start: the Story Points Window. The Story Points Window lists all the structural elements in your story with a space to illustrate how that element will appear or come into play in your story. This ensures that there are no structural holes caused by forgetting to include an important point.

Normally the Story Points Window is used after you have already created a structural storyform using the Story Engine, and then can refer to each story point and work out how to implement it in your story. But, again, this puts structure before creativity and flies in the face of the excitement and enthusiasm of getting on with your writing.

So, the tip is to begin with the Story Points Window before making even a single structural choice! Here’s how you do it:

First, open the Story Points Window from the desktop in Dramatica Pro or from the tool bar icon in Dramatica Story Expert. You will find that it contains the names of all the story points tracked by the Story Engine, but doesn’t yet have the structural choice you made listed. (See picture above)

The first column shows the name of each story point. The second column will list your structural choice for that story point when you eventually make it. The third column provides a definition of each story point. The fourth column is where you would normally illustrate how each story point will show up in your story – but we’re going to do it differently….

Start at the top of the list of story points. The first story point is called Resolve. Its definition reads, the ultimate disposition of the Main Character to Change or Remain Steadfast.

If this story point makes sense to you in regard to your story, then in the illustration column, describe how it shows up in your story. If it doesn’t yet connect to your story, skip it and move on to the next.

The difference from the standard way the software says you should go about things is that you don’t have to first make the structural choices directly from all the ideas you have floating around in your head. Rather, first you focus on a story point and describe how it applies to your story’s subject matter, rather than to your structure. Then later you’ll go back and make the structural choices, but when you do, you’ll see what you’ve already written in the Illustration column and the choice will be much easier to make.

As an example of this, you’ll come across a story point called Overall Story Domain which is defined as the general area in which the Overall Story’s problem resides. If you do it Dramatica’s way, you are asked to choose which of four items best describes your Overall Story’s Domain: Situation, Activity, Attitude or Manipulation.

Now that can be a tough choice to make if you haven’t studied exactly what each of these terms means. And trying to get into a mind set where you can sort through all the material you have swirling around in your head about your story to find the answer to that question can sometimes be impossible.

But if you forget about the actual structural choices until later and instead just describe in plain language the general area in which the Overall Story’s problem resides you might write something like, My story’s problem is about traveling to the underworld to recover a talisman that will prevent an alien invasion , then later it will be a lot easier to say, “Well, that is more an Activity than a Situation, Attitude or Manipulation.” Entering the subject matter first makes the structural choice easier later.

So, go through the entire list of Story Points and when you reach the bottom, go through the list one more time and see if you can now write something about the story points you left blank the first time around. Why? Because sometimes the process of organizing your thoughts and getting your ideas out of your head is enough to open new insights.

Once you’ve filled in all the illustrations you can, then go to the Story Guide which is the step by step set of structural questions. You can find it as a button on the Dramatica Pro desktop or in the tool bar icons in Story Expert.

Now, when you go to a structural question, instead of having to face it directly, you’ll find that the illustrations you put in the Story Points window automatically show up on each structural question. So, you can refer to that material and make the structural choice that best describes it. And, of course, you can also revise your illustrations as you go – as you come to know your story better.

Using this method, you’ll never have to run into the wall of structure, but can follow your Muse and then describe what she had told you.

Write Your Novel Step by Step

Write Your Novel Step by Step