Every once in a while I write an article about the Dramatica theory of narrative structure that zooms right down to the subatomic level.

Such articles have absolutely no practical value to writers but, being a narrative scientist, it is a means demonstrating the depth and complexity of the Dramatica theory to my fellow self-proclaimed wizards of space and time.

Case in point: here is a reprint of the very first post I made to my Dramatica blog so many years ago…

~ Caution – Deep Narrative Theory Ahead ~

What’s “Ability” have to do with story structure?

In this article I’m going to talk about how the Dramatica Theory of Narrative Structure uses the term “ability” and how it applies not only to story structure and characters but to real people, real life and psychology as well.

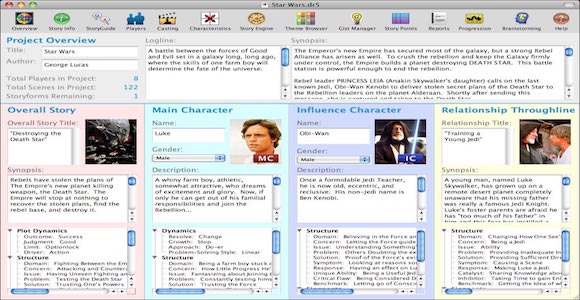

Ability is one of the dramatic elements that the Dramatica software define your story’s message and thematic conflict. There are sixty-four thematic elements in Dramatica – a whole spectrum of human traits and qualities that might be good or bad ones to have, depending upon the story.

If you look in Dramatica’s “Periodic Table of Story Elements” chart (you can download a free PDF of the chart at http://storymind.com/free-downloads/ddomain.pdf ) you’ll find “ability” in one of the little squares. To locate it, look in the family called the “Physics” class in the upper left-hand corner of the chart and examine the very smallest items listed there. You’ll find it in a group of four dramatic elements, “Knowledge, Thought, Ability and Desire”.

To begin with, a brief word about the Dramatica chart itself. The chart is sort of like a Rubik’s Cube. It holds all the elements which must appear in every complete story to avoid holes. Conceptually, you can twist it and turn it, just like a Rubik’s Cube, and when you do, it is like winding up a clock – you create dramatic potential.

How is this dramatic potential created? The chart represents all the categories of things we think about. Notice that the chart is nested, like wheels within wheels. That’s the way our minds work. And if we are to make a solid story structure with no holes, we have to make sure all ways of thinking about the story’s central problem or issues are covered.

So, the chart is really a model of the mind. When you twist it and turn it represents the kinds of stress (and experience) we encounter in everyday life. Sometimes things get wound up as tight as they can and get stuck there. And this is where a story always starts. Anything before that point is backstory, anything after it is story.

The story part is the process of unwinding that tension. So why does a story feel like tension is building, rather than lessening? This is because stories are about the forces that bring a person to change or, often, to a point of change.

As the story mind unwinds, it puts more and more pressure on the main character (who may be gradually changed by the process or may remain intransigent until he changes all at once). It’s kind of like the forces that create earthquakes. Tectonic plates push against each other driven by a background force (the mantle). That force is described by the wound up Dramatica chart of the story mind.

Sometimes, in geology, this force gradually raises or lowers land in the two adjacent plate. Other times it builds up pressure until things snap all at once in an earthquake. So too in psychology, people (characters) are sometimes slowly changed by the gradual application of pressure as the story mind clock is unwinding; other times that pressure applied by the clock mechanism just builds up until the character snaps in Leap Of Faith – that single “moment of truth” in which a character must decide either to change his ways or stick by his guns believing his current way is stronger than the pressure bought to bear – he believes he just has to outlast the forces against him.

Sometimes he’s right to change, sometimes he’s right to remain steadfast, and sometimes he’s wrong. But either way, in the end, the clock has unwound and the potential has been balanced.

Hey, what happened to “ability”? Okay, okay, I’m getting to that….

The chart (here we go again!) is filled with semantic terms – things like Hope and Physics and Learning and Ability. If you go down to the bottom of the chart in the PDF you’ll see a three-dimensional representation of how all these terms are stacked together. In the flat chart, they look like wheels within wheels. In the 3-D version, they look like levels.

The chart (here we go again!) is filled with semantic terms – things like Hope and Physics and Learning and Ability. If you go down to the bottom of the chart in the PDF you’ll see a three-dimensional representation of how all these terms are stacked together. In the flat chart, they look like wheels within wheels. In the 3-D version, they look like levels.

These “levels” represent degrees of detail in the way the mind works. At the most broadstroke level (the top) there are just four items – Universe, Physics, Mind and Psychology. They are kind of like the Primary Colors of the mind – the Red, Blue, Green and Saturation (effectively the addition of something along the black/white gray scale).

Those for items in additive color theory are four categories describing what can create a continuous spectrum. In a spectrum is really kind of arbitrary where you draw the line between red and blue. Similarly, Universe, Mind, Physics and Psychology are specific primary considerations of the mind.

Universe is the external state of things – our situation or envirnoment. Mind is the internal state – an attitude, fixation or bias. Physics looks at external activities – processes and mechanisms. Psychology looks at internal activities – manners of thinking in logic and feeling.

Beneath that top level of the chart are three other levels. Each one provides a greater degree of detail on how the mind looks at the world and at itself. It is kind of like adding “Scarlet” and “Cardinal” as subcategories to the overall concept of “Red”.

Now the top level of the Dramatica chart describe the structural aspects of “Genre” Genre is the most broadstroke way of looking at a story’s structure. The next level down has a bit more dramatic detail and describes the Plot of a story. The third level down maps out Theme, and the bottom level (the one with the most detail) explores the nature of a story’s Characters.

So there you have the chart from the top down, Genre, Plot, Theme and Characters. And as far as the mind goes, it represents the wheels within wheels and the sprectrum of how we go about considering things. In fact, we move all around that chart when we try to solve a problem. But the order is not arbitrary. The mind has to go through certain “in-betweens” to get from one kind of consideration to another or from one emotion to another. You see this kind of thing in the stages of grief and even in Freud’s psycho-sexual stages of development.

All that being said now, we finally return to Ability – the actual topic of this article. You’ll find Ability, then, at the very bottom of the chart – in the Characters level – in the upper left hand corner of the Physics class. In this article I won’t go into why it is in Physics or why it is in the upper left, but rest assured I’ll get to that eventually in some article or other.

Let’s now consider “Ability” in its “quad” of four Character Elements. The others are Knowledge, Thought, Ability and Desire. I really don’t have space in this article to go into detail about them at this time, but suffice it to say that Knowledge, Thought, Ability and Desire are the internal equivalents of Universe, Mind, Physics and Pyschology. They are the conceptual equivalents of Mass, Energy, Space and Time. (Chew on that for awhile!)

So the smallest elements are directly connect (conceptually) to the largest in the chart. This represents what we call the “size of mind constant” which is what determines the scope of an argument necessary to fill the minds of readers or an audience. In short, there is a maximum depth of detail one can perceive while still holding the “big picture” in one’s mind at the very same time.

Ability – right….

Ability is not what you can do. It is what you are “able” to do. What’s the difference? What you “can” do is essentially your ability limited by your desire. Ability describes the maximum potential that might be accomplished. But people are limited by what they should do, what they feel obligated to do, and what they want to do. If you take all that into consideration, what’s left is what a person actually “can” do.

Ability is not what you can do. It is what you are “able” to do. What’s the difference? What you “can” do is essentially your ability limited by your desire. Ability describes the maximum potential that might be accomplished. But people are limited by what they should do, what they feel obligated to do, and what they want to do. If you take all that into consideration, what’s left is what a person actually “can” do.

In fact, if we start adding on limitations you move from Ability to Can and up to even higher levels of “justification” in which the essential qualities of our minds, “Knowledge, Thought, Ability and Desire” are held in check by extended considerations about the impact or ramifications of acting to our full potential.

One quad greater in justification you find “Can, Need, Want, and Should” in Dramatica’s story mind chart. Then it gets even more limited by Responsibility, Obligation, Commitment and Rationalization. Finally we end up “justifying” so much that we are no longer thinking about Ability (or Knowledge or Thought or Desire) but about our “Situation, Circumstance, Sense of Self and State of Being”. That’s about as far away as you can get from the basic elements of the human mind and is the starting point of where stories begin when they are fully wound up. (You’ll find all of these at the Variation Level in the “Psychology” class in the Dramatica chart, for they are the kinds of issues that most directly affect each of our own unique brands of our common human psychology.

A story begins when the Main Character is stuck up in that highest level of justification. Nobody gets there because they are stupid or mean. They get there because their unique life experience has brought them repeated exposures to what appear to be real connections between things like, “One bad apple spoils the bunch” or “Where there’s smoke , there’s fire.”

These connections, such things as – that one needs to adopt a certain attitude to succeed or that a certain kind of person is always lazy or dishonest – these things are not always universally true, but may have been universally true in the Main Character’s experience. Really, its how we all build up our personalities. We all share the same basic psychology but how it gets “wound up” by experience determines how we see the world. When we get wound up all the way, we’ve had enough experience to reach a conclusion that things are always “that way” and to stop considering the issue. And that is how everything from “winning drive” to “prejudice” is formed – not by ill intents or a dull mind buy by the fact that no two life experiences are the same.

The conclusions we come to, based on our justifications, free out minds to not have to reconsider every connection we see. If we had to, we’d become bogged down in endlessly reconsidering everything, and that just isn’t a good survival trait if you have to make a quick decision for fight or flight.

So, we come to certain justification and build upon those with others until we have established a series of mental dependencies and assumptions that runs so deep we can’t see the bottom of it – the one bad brick that screwed up the foundation to begin with. And that’s why psychotherapy takes twenty years to reach the point a Main Character can reach in a two hour movie or a two hundred page book.

Now we see how Ability (and all the other Dramatica terms) fit into story and into psychology. Each is just another brick in the wall. And each can be at any level of the mind and at any level of justification. So, Ability might be the problem in one story (the character has too much or too little of it) or it might be the solution in another (by discovering an ability or coming to accept one lacks a certain ability the story’s problem – or at least the Main Character’s personal problem – can be solved). Ability might be the thematic topic of one story and the thematic counterpoint of another (more on this in other articles).

Ability might crop up in all kinds of ways, but the important thing to remember is that wherever you find it, however you use it, it represents the maximum potential, not necessarily the practical limit that can be actually applied.

Well, enough of this. To close things off, here’s the Dramatica Dictionary description of the world Ability that Chris and I worked out some twenty years ago, straight out of the Dramatica diction (available online at http://storymind.com/dramatica/dictionary/index.htm :

Ability • Most terms in Dramatica are used to mean only one thing. Thought, Knowledge, Ability, and Desire, however, have two uses each, serving both as Variations and Elements. This is a result of their role as central considerations in both Theme and Character

[Variation] • dyn.pr. Desire<–>Ability • being suited to handle a task; the innate capacity to do or be • Ability describes the actual capacity to accomplish something. However, even the greatest Ability may need experience to become practical. Also, Ability may be hindered by limitations placed on a character and/or limitations imposed by the character upon himself. • syn. talent, knack, capability, innate capacity, faculty, inherant proficiency

[Element] • dyn.pr. Desire<–>Ability • being suited to handle a task; the innate capacity to do or be • An aspect of the Ability element is an innate capacity to do or to be. This means that some Abilities pertain to what what can affect physically and also what one can rearrange mentally. The positive side of Ability is that things can be done or experienced that would otherwise be impossible. The negative side is that just because something can be done does not mean it should be done. And, just because one can be a certain way does not mean it is beneficial to self or others. In other words, sometimes Ability is more a curse than a blessing because it can lead to the exercise of capacities that may be negative • syn. talent, knack, capability, innate capacity, faculty, inherent proficiency

Melanie Anne Phillips

Creator, StoryWeaver

Co-creator, Dramatica