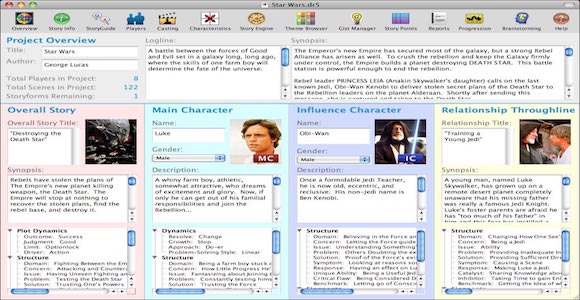

What is Dramatica?

Dramatica is a theory of story that offers both writers and critics a clear view of what story structure is and how it works. Dramatica is also the inspiration behind the line of story development software products that bear its name.

The central concept of the Dramatica theory is a notion called the “Story Mind.” In a nutshell, this simply means that every story has a mind of its own – its own personality; its own psychology. A story’s personality is developed by an author’s style and subject matter; its psychology is determined by the underlying dramatic structure.

The Story Mind

The Story Mind is at the heart of Dramatica, and everything else about the theory grows out of that. If you don’t buy into it, at least a little, then you’re not going to find much use for the rest of this book. So let’s take look into the Story Mind right off the bat to see if it is worth your while to keep reading…

Simply put, the Story Mind means that we can think of a story as if it were a person. The storytelling style and the subject matter determine the story’s personality, and the underlying dramatic structure determines its psychology.

Now the personality of a story is a touchy-feely thing, while the psychology is a nuts-and-bolts mechanical thing. Let’s consider the personality part first, and then turn our attention to the psychology.

Like anyone you meet, a story has a personality. And what makes up a personality? Well, everything from the subject matter a person talks about to their attitude toward life. Similarly, a story might be about the Old West or Outer Space, and its attitude could be somber, sneaky, lively, hilarious, or any combination of other human qualities.

Is this a useful perspective? Can be. Many writers get so wrapped up in the details of a story that they lose track of the overview. For example, you might spend all kinds of time working out the specifics of each character’s personality yet have your story take a direction that is completely out of character for its personality. But if you step back every once and a while and think of the story as a single person, you can really get a sense of whether or not it is acting in character.

Imagine that you have invited your story to dinner. You have a pleasant conversation with it over the meal. Of course, it is more like a monologue because your story does all the talking – just as it will to your audience or reader.

Your story is a practical joker, or a civil war buff (genre), and it talks about what interests it. It tells you a story about a problem with some endeavor (plot) in which it was engaged. It discusses the moral issues (theme) involved and its point of view on them. It even divulges the conflicting drives (characters) that motivated it while it tried to resolve the difficulties.

You want to ask yourself if it’s story makes sense. If not, you need to work on the logic of your story. Does it feel right, as if the Story Mind is telling you everything, or does it seem like it is holding something back? If so, your story has holes that need filling. And does your story hold your interest for two hours or more while it delivers it’s monologue? If not, it’s going to bore it’s captive audience in the theater, or the reader of its report (your book), and you need to send it back to finishing school for another draft.

Again, authors get so wrapped up in the details that they lose the big picture. But by thinking of your story as a person, you can get a sense of the overall attraction, believability, and humanity of your story before you foist it off on an unsuspecting public.

There’s much more we’ll have to say about the personality of the Story Mind and how to leverage it to your advantage. But, our purpose right now is just to see if this book might be of use to you. So, let’s examine the other side of the Story Mind concept – the story’s psychology as represented in its structure.

The Dramatica theory is primarily concerned with the structure of a story. Everything in that structure represents an aspect of the human mind, almost as if the processes of the mind had been made tangible and projected out externally for the audience to observe.

Do you remember the model kit of the “Visible Man?” It was a 12″ human figure made out of clear plastic so you could see the skeleton and all the organs on the inside. Well that is how the Story Mind works. it takes the processes of the human mind, and turns them into characters, plot, theme, and genre, so we can study them in detail. In this way, an author can provide understanding to an audience of the best way to deal with problems. And, of course, all of this is wrapped up and disguised in the particular subject matter, style, and techniques of the storyteller.

Now this makes it sound as if the real meat of a story, the real people, places, events, and topics, are just window dressing to distract the audience from the serious business of the structure. But that’s not what we’re saying here. In fact, structure and storytelling work side by side, hand in hand, to create an audience/reader experience that transcends the power of either by itself.

Therefore, structure and storytelling are neither completely dependent upon each other, nor are they wholly independent. One structure might be told in a myriad of ways, like West Side Story and Romeo and Juliet. Similarly, any given group of characters dealing with a particular realm of subject matter might be wrapped around any number of different structures, like weekly television series.

But let’s get back to the nature of the structure itself and to the elements that make up the Story Mind. If characters, plot, theme, and genre represent aspects of the human mind made tangible, what are they?

Characters represent the conflicting drives of our own minds. For example, in our own minds, our reason and our emotions are often at war with one another. Sometimes what makes the most sense doesn’t feel right at all. And conversely, what feels so right might not make any sense at all. Then again, there are times when both agree and what makes the most sense also feels right on.

Reason and Emotion then, become two archetypal characters in the Story Mind that illustrate that inner conflict that rages within ourselves. And in the structure of stories, just as in our minds, sometimes these two basic attributes conflict, and other times they concur.

Theme, on the other hand, illustrates our troubled value standards. We are all plagued with uncertainties regarding the right attitude to take, the best qualities to emulate, and whether our principles should remain fixed and constant or should bend in context to particular circumstances.

Plot compares the relative value of the methods we might employ within our minds in our attempt to press on through these conflicting points of view on the way toward a mental consensus.

And genre explores the overall attitude of the Story Mind – the points of view we take as we watch the parade of our own thoughts unfold, and the psychological foundation upon which our personality is built.