The Story Mind concept is a way of visualizing story structure that sees every story as having a mind of its own and the characters within it as facets of that overall mind. So, one character represents the Intellect of the Story Mind and another functions as its Skepticism, for example.

Of course, this is just at a structural level – the mechanics of the story. Naturally, characters also have to be real people in their own right so the readers or audience can identify with them.

But, structurally, the archetypes we see in stories are very like the basic mental attributes we all possess, made tangible as avatars of the Story Mind’s thought processes.

Well, that’s a pretty radical concept. So before asking any writer to invest his or her time in a concept as different as the Story Mind, it is only fair to provide an explanation of why such a thing should exist. To do this, let us look briefly into the nature of communication between an author and an audience and see if there is supporting evidence to suggest that character archetypes are facets of a greater Story Mind.

When an author tells a tale, he simply describes a series of events that both makes sense and feels right. As long as there are no breaks in the logic and no mis-steps in the emotional progression, the structure of the tale is sound.

Now, from a structural standpoint, it really doesn’t matter what the tale is about, who the characters are, or how it turns out. The tale is just a truthful or fictional journey that starts in one situation, travels a straight or twisting path, and ends in another situation.

The meaning of a tale amounts to a statement that if you start from “here,” and take “this” path, you’ll end up “here.” The message of a tale is that a particular path is a good or bad one, depending on whether the ending point is better or worse than the point of departure.

This structure is easily seen in the vast majority of familiar fairy “tales.” Tales have been used since the first storytellers practiced their craft. In fact, many of the best selling novels and most popular motion pictures of our own time are simple tales, expertly told.

In a structural sense, tales have power in that they can encourage or discourage audience members from taking particular actions in real life. The drawback of a tale is that it speaks only in regard to that specific path.

But in fact, there are many paths that might be taken from a given point of departure. Suppose an author wants to address those as well, to cover all the alternatives. What if the author wants to say that rather than being just a good or bad path, a particular course of action the best or worst path of all that might have been taken?

Now the author is no longer making a simple statement, but a “blanket” statement. Such a blanket statement provides no “proof” that the path in question is the best or worst, it simply says so. Of course, an audience is not likely to be moved to accept such a bold claim, regardless of how well the tale is told.

In the early days of storytelling, an author related the tale to his audience in person. Should he aspire to wield more power over his audience and elevate his tale to become a blanket statement, the audience would no doubt cry, “Foul!” and demand that he prove it. Someone in the audience might bring up an alternative path that hadn’t been included in the tale.

The author might then counter that rebuttal to his blanket statement by describing how the path proposed by the audience was either not as good or better (depending on his desired message) than the path he did include.

One by one, he could disperse any challenges to his tale until he either exhausted the opposition or was overcome by an alternative he couldn’t dismiss.

But as soon as stories began to be recorded in media such as song ballads, epic poems, novels, stage plays, screenplays, teleplays, and so on, the author was no longer present to defend his blanket statements.

As a result, some authors opted to stick with simple tales of good and bad, but others pushed the blanket statement tale forward until the art form evolved into the “story.”

A story is a much more sophisticated form of communication than a tale, and is in fact a revolutionary leap forward in the ability of an author to make a point. Simply put, when creating a story, and author starts with a tale of good or bad, expands it to a blanket statement of best or worst, and then includes all the reasonable alternatives to the path he is promoting to preclude any counters to his message. In other words, while a tale is a statement, a story becomes an argument.

Now this puts a huge burden of proof on an author. Not only does he have to make his own point, but he has to prove (within reason) that all opposing points are less valid. Of course, this requires than an author anticipate any objections an audience might raise to his blanket statement. To do this, he must look at the situation described in his story and examine it from every angle anyone might happen to take in regard to that issue.

By incorporating all reasonable (and valid emotional) points of view regarding the story’s message in the structure of the story itself, the author has not only defended his argument, but has also included all the points of view the human mind would normally take in examining that central issue. In effect, the structure of the story now represents the whole range of considerations a person would make if fully exploring that issue.

In essence, the structure of the story as a whole now represents a map of the mind’s problem solving processes, and (without any intent on the part of the author) has become a Story Mind.

And so, the Story Mind concept is not really all that radical. It is simply a short hand way of describing that all sides of a story must be explored to satisfy an audience. And, and if this is done, the structure of the story takes on the nature of a single character.

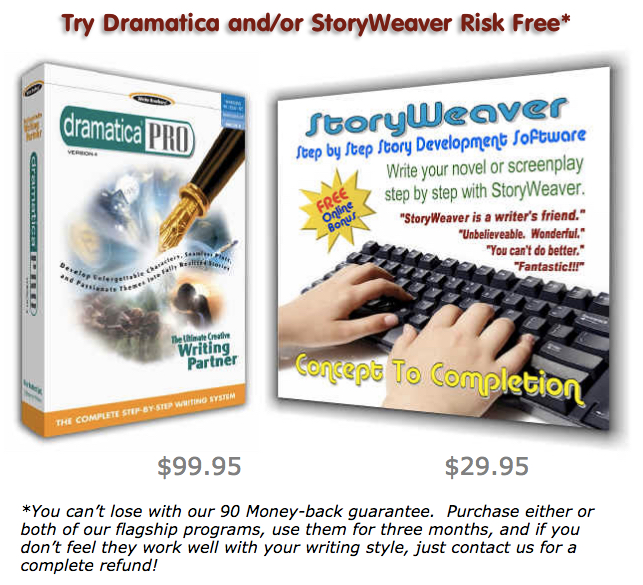

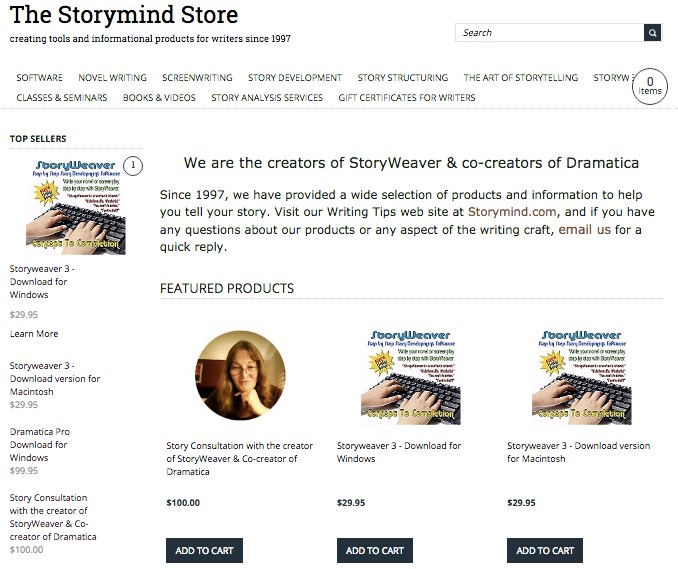

The Story Mind concept is drawn from the Dramatica Theory of Story Structure. Learn more about Dramatica at Storymind.com

Learn more about the Story Mind

Melanie Anne Phillips

Creator, StoryWeaver

Co-Creator, Dramatica

For fans of the Dramatica Story Structure Theory (and software):

For fans of the Dramatica Story Structure Theory (and software):