Of all your cast, there is one very special player: the Main Character. Your Main Character is the one your story seems to be about – the one with whom your readers most identify – in short, the single most important character in your novel.

You probably already know who your Main Character is. If, so, you’ll find this step opens opportunities to avoid stereotyping him or her. If you haven’t yet selected your Main Character, this step will help you choose one from your cast list.

First, your Main Character is not necessarily your protagonist. While the protagonist is the prime mover of the effort to achieve the story goal, the Main Character is the one who grapples with an inner dilemma, personal issue or has some aspect of his or her belief system come under attack.

Most writers combine these two functions into a single player (a hero) who is both protagonist and Main Character in order to position their readers right at the heart of the action, as in the Harry Potter series.

Still, there are good reasons for not always blending the two. In the book and movie To Kill A Mockingbird, the protagonist is Atticus – a southern lawyer trying to acquit a young black man wrongly accused of rape. That is the basic plot of the story.

But the Main Character is Atticus’ young daughter, Scout. While the overall story is about the trial, that is really just a background to Scout’s experiences as we see prejudice through her eyes – a child’s eyes.

In this way, the author (Dee Harper) distances us from the incorruptible Atticus so that we do not feel all self-righteous. And, by making Scout effectively prejudiced against Boo Radley (the scary “boogie man” who lives down the street), we see how easily we can all become prejudiced by fearing what we really know nothing about.

In the end, Boo turns out to be Scout’s secret protector, and the story’s message about both the evils and ease of prejudice is made.

Your story may be best suited to center around a typical hero, especially if it is an action story or physical journey story. But if you are writing more of an exploration novel in which the plot unfolds as a background against which a personal journey of self-discovery or a resolution of personal demons is told, then separating your Main Character from the protagonist (and the heart of the action) may serve you better.

Armed with this understanding, review the cast you have chosen for your novel. If you have already selected a Main Character, see if they are a hero who is also the protagonist, driving the action. If so, consider splitting those functions into two players to see if it might enhance your story for your readers. If you have already set up a separate Main Character and protagonist, consider combining them into a hero, to see if that might streamline your story.

If you have not yet chosen a Main Character and/or a protagonist, review your cast list to see if one player would best do both jobs or if one would better drive the plot and the other would better carry the message.

When you have made your choices, write a brief paragraph about your Main Character and/or protagonist to explain how those two functions are satisfied by your chosen character or characters.

This article is one of the 200 interactive steps in

Step by Step Story Development Software

Step by Step Story Development Software

Build your Story’s World, who’s in it, what happens to them and what it all means with StoryWeaver! With over 200 interactive Story Cards, StoryWeaver takes you step by step through the entire process – from concept to completion.

Build your Story’s World, who’s in it, what happens to them and what it all means with StoryWeaver! With over 200 interactive Story Cards, StoryWeaver takes you step by step through the entire process – from concept to completion.

Just $29.95 ~ Click here to learn more or to purchase…

The protagonist and antagonist may not be who you think they are. For one thing, a protagonist is not necessarily the hero of a story. Structurally speaking, the protagonist is the one who shakes up the status quo – that’s the “pro” part, while the antagonist is the one who tries to stop that effort or put it back the way it was.

The protagonist and antagonist may not be who you think they are. For one thing, a protagonist is not necessarily the hero of a story. Structurally speaking, the protagonist is the one who shakes up the status quo – that’s the “pro” part, while the antagonist is the one who tries to stop that effort or put it back the way it was.

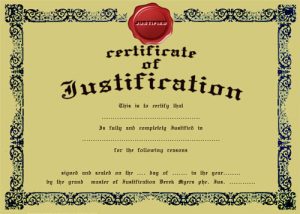

A story begins when the Main Character is stuck up in the highest level of justification. Nobody gets there because they are stupid or mean. They get there because their unique life experience has brought them repeated exposures to what appear to be real connections between things like, “One bad apple spoils the bunch” or “Where there’s smoke , there’s fire.”

A story begins when the Main Character is stuck up in the highest level of justification. Nobody gets there because they are stupid or mean. They get there because their unique life experience has brought them repeated exposures to what appear to be real connections between things like, “One bad apple spoils the bunch” or “Where there’s smoke , there’s fire.”