Most writers are not story theorists, and don’t want to be. Still, an understanding of the way stories work can help support a writer’s instincts to make sure a flawed structure won’t get in the way of the creativity.

So what is story structure? It is a map of the way people go about solving different kinds of problems, and a message by the author as to which methods are better than others.

Where did story structure come from? Well, for thirty thousand years or so we’ve been telling stories, but nobody every really invented story structure. Rather, story structure just kind of emerged as a byproduct of the effort to describe how individuals deal with problems and how they interact with others when dealing with problems that affect more than one person.

Story structure first appeared as the conventions of storytelling –

Now a lot of writers wanted something a little more tangible –

These kinds of inquires led to the development of everything from the concept of a three-

Some twenty-

In our research we came to believe that every individual has certain common traits we all share, such as Reason and Skepticism. And we each use all of them to try and solve our personal problems. But when we gather together in groups to solve problems of common concern, we begin to specialize so that one person emerges as the Voice of Reason for the group, and another comes to be the group’s resident Skeptic.

In this way, the group can get greater depth or resolution on how to go about solving complex problems than if all the members worked as general practitioners, all trying to do all the jobs, each and every one.

It was our feeling this sort of thing naturally occurs whenever we gather toward a common purpose because, in a sense, it is a good survival trait for the group as a whole, and therefore for everyone in that group.

Well, there’s a lot more to our theory of story structure than that, but armed with this initial breakthrough concept, we spent about three years trying to build a model of story structure. And the end result was an interactive model of all the different kinds of traits we all share, both large and very small, and how they hang together. Those, we felt, were the elements of structure, and we created a kind of periodic table of story structure to show their dramatic properties and how they all related to one another.

And beyond that, we discovered that there were dynamics built right into the conventions of story structure that could only be seen if you looked at it as a Story Mind. We cataloged those and how the whole structure was really a very flexible affair in which truisms were no longer needed because you could create very specific structures for just about any issue you might like to explore as an author.

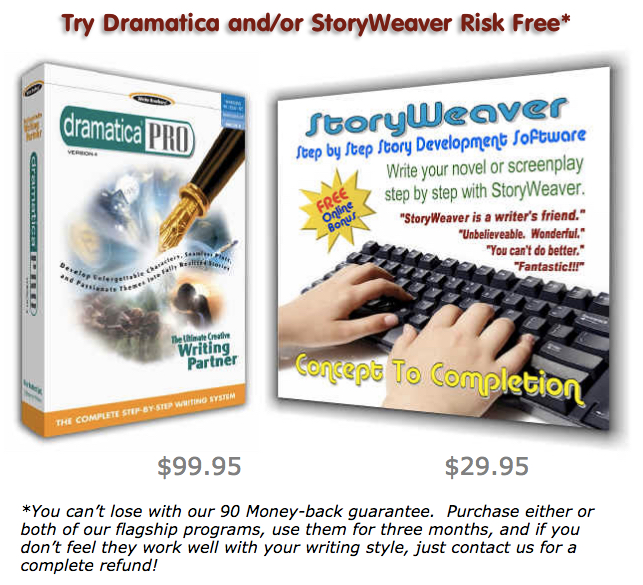

Eventually, we converted those relationships into a software-

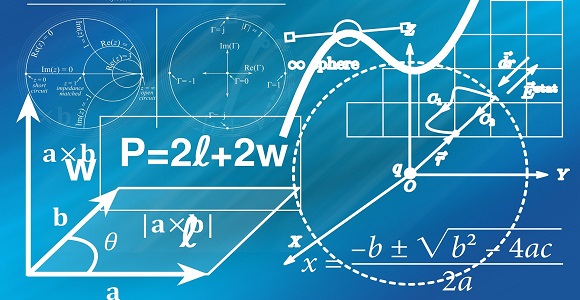

Now, if you own the Dramatica software, you’ve probably noticed it presents a flat chart called the “Theme Browser” that shows how dramatic subjects relate to one another. Though it isn’t in the software, there is also a 3D projection of the flat chart that looks something like a Rubik’s Cube on steroids, or a super-

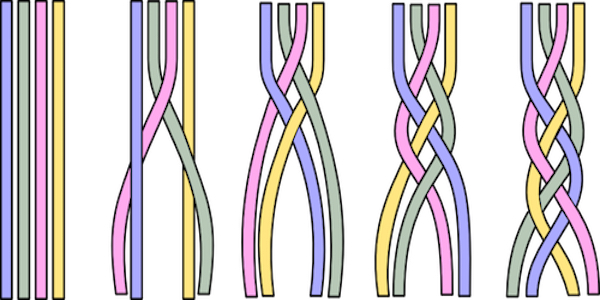

The flat chart provides a map of the elements that make up stories and the 3D chart is the best way to understand the “winding up” process of dramatic tension of your story. Essentially, when you run into troubles in life, you try one kind of a solution after another –

Whenever you try one solution instead of another, you not only bring the new one to the front but simultaneously push the old one into the background or onto the back burner. In the 3D chart, we call that “flipping and rotating” because sometimes you flip positions of dramatic items and other times you rotate them to change the order in which they are applied. After all, some problems are caused by using the wrong process and other problems are caused by using the right processes but in the wrong sequence.

The Story Engine at the heart of the Dramatica software tracks all of those elements to make sure no dramatic “rules” are broken. What’s a Dramatic Rule? As an analogy, you can twist and turn a Rubik’s Cube, but you can’t pluck one of the little cubes out of it and swap it’s position with another little cube. In other words, you can create all kinds of patterns, but you can’t break structure. Similarly in stories, you can create all kinds of dramatic patterns, but you can’t just drop story elements wherever you want –

When you answer questions about your story in Dramatica, you are expressing your dramatic intent –

Every time you make a choice, you are saying, “I want my story to look like this, as opposed to that.” You are choosing just as much what you DON’T want in your story as what you do.

The choices are cumulative –

Imagine –

So, what is structure? Structure is nothing more than making a point, either logistically or emotionally or both. Many stories don’t need structure because they are not about making a larger point or having a message, but are designed to be experiences without any greater overall meaning.

We call experiential structures “Tales” and greater meaning structures “Stories.” So, if you have an unbroken chain of events that makes sense coupled with a series of emotional experiences that don’t violate the way people really feel, that’s all you need to have a complete Tale structure. But, to have a complete Story structure, each event and experience is part of an overall pattern that becomes clear by the time the story is over. There is nothing better or worse about a Tale compared to a Story, but authors of Stories take upon themselves a more demanding rigor.

Historically, it has been easy to miss a step in the events of a tale or a beat in the emotional journey. And, it has been even harder to ensure that each of those dramatic moments contributes to the greater meaning in a story. That’s why Dramatica’s Story Engine was built –

You can try out the Story Engine for free! The demo version of Dramatica is fully functional, other than saving your work. So if you want to try some of the questions and play around with the other tools, you can download the demo here and get everything the Story Engine has to offer except for saving your work to continue with it in later sessions.

Honestly, you may find Dramatica a little daunting, as it is extremely powerful and wide ranging with all kinds of features and functions. And, it is built on our theory of story structure, which (though elegant) is also extensive and detailed. Nonetheless, my feelings are that the more you learn about story structure in Dramatica , the more you have improved your ability to visualize and actualize your story. So, my advice is to give it a try for free. All you have to lose is a little itsy bitsy crumb of time, but what you have to gain is a much deeper and powerful understanding of stories and how to structure them.

Click here for more Dramatica details and Demo

Here’s something else I made for writers…