By Melanie Anne Phillips

Here’s a flashback article from the early days of the Dramatica theory of narrative structure back in the mid 1990s. It is the first article I wrote in a series of “Constructive Criticisms” in which I showed how Dramatica could have improved highly successful movies and books, not just ones that were obviously flawed.

Here’s a flashback article from the early days of the Dramatica theory of narrative structure back in the mid 1990s. It is the first article I wrote in a series of “Constructive Criticisms” in which I showed how Dramatica could have improved highly successful movies and books, not just ones that were obviously flawed.

We knew Dramatica was a powerful new way to look at structure. And to convey this to others, we figured that while anybody might show how to make a bad story better, we had the method to show how to make a great story superlative.

So, here’s the original article as it appeared in the first edition of our Storyforming Newsletter…

Jurassic Park: Building A Better Dinosaur!

Jurassic Park is wonderfully entertaining. The concepts are intriguing, the visuals stunning. Everything it does, it does well. Unfortunately, it doesn’t do enough. There are parts missing, little bits of story DNA that are needed to complete the chain. To be fair, these problems largely result from the mostly faithful adherence to the dramatic structure and dynamics of the book upon which the movie is based.

Storyform, the structure and dynamics of a story, is not medium dependent. What works in one medium will work in all others. Storytelling, however, must vary significantly to take advantage of the strengths and avoid the weaknesses inherent in any format. Jurassic Park makes this storytelling translation very well, but the flawed dramatics were nearly lifted intact, shackling the movie just like the book with a Pterodactyl hanging `round its neck.

Yet criticisms are a dime a dozen. Suggestions for improvement are much more rare. Fortunately that is the strong suit of the Dramatica theory. Here is one plan for building a better dinosaur.

Dramatica Background

As a starting point, Dramatica denotes a difference between a Tale and a Story. A Tale describes a series of events that lead to success or failure. It carries the message that a particular way of going about solving the problem is or is not a good one. But a Story is an argument that there is only one right way to solve a problem. It is a much more potent form that seeks to have the audience accept the author’s conclusions.

To gain an audience’s acceptance, an argument (Story) must appeal to both logic and feeling. To make the logical part of this argument, all the inappropriate ways a problem might be approached need to be addressed and shown to fail. Each one must be given its due and shown not to work except the one touted by the author. This is accomplished by looking at the characters and the plot objectively, much like a general on a hill watching a battle down below. The big picture is very clear and the scope and ramifications of the individual soldiers can be seen in relationship to the entire field.

However, to make the emotional part of the argument, the audience must become involved in the story at a personal level. To this end, they are afforded a Subjective view of the story through the eyes of the Main Character. Here they get to participate in the battle as if they were actually one of the soldiers in the trenches. It is the differential between the Subjective view of the Main Character and the Objective view of the whole battle that generates dramatic tension from which the message of the story is created.

By comparing the two views, the argument is made to the audience that the Main Character must change to accommodate the big picture, or that the Main Character is on the right track and must hold on to their resolve if they hope to succeed. Of course, the Main Character cannot see the big picture, so they must make a leap of faith near the end of the story, deciding if they want to stick it out or change.

Now this relationship between the Main Character and the Objective story makes them a very special character. In fact, they hold the key to the whole battle. They are the crucial element in the dramatic web who (through action or inaction) can wrap the whole thing up or cause it to fall apart. As a result, the personal problems they face reflect the nature of the Objective problem of the story at large.

To the audience there are two problems in a story. One is the Objective problem that everyone is concerned with; the other is the Subjective problem that the Main Character is personally concerned with. Although the problems may be greatly different in the way they are manifest, they both hinge on the crucial element in the Main Character as their common root. So, to be a complete argument a story must explore an Objective AND a Subjective problem, and show how they are both related to the same source.

Jurassic Park Analysis:

Jurassic Park attempts to be a story (not a tale) but does not make it because its exploration of the Subjective problem is lacking.

The Objective problem is clearly shown to be caused by the relationship of Order to Chaos. The message of the logical side of the argument is that the more you try to control something, the more you actually open yourself up to the effects of chaos. As Princess Leia put it to the Gran Mof Tarkin in Star Wars, “The more you tighten your grip, the more star systems will slip through your fingers.”

Since Order is actually the problem, the Chaos must be the solution. This is vaguely alluded to in Jurassic Park when the Tyrannosaurus wipes out the Raptors, unknowingly saving the humans. Although the point is not strongly stated, it is sort of there. We will come back to this point later to show how it should have been a much more dramatically integral event than it was. The important concept at the moment is that as far as it goes, the Objective Storyline is fairly close to what it should be, which is true of most action-oriented stories.

It is the Subjective Storyline that fails to fulfill its dramatic mandate in Jurassic Park. To see how we must go back to the very beginning of the film, to our Main Character, Dr. Alan Grant. Since Dr. Grant contains the crucial element, we would expect him to intersect the Objective Story’s problem by representing Order or Chaos. Clearly the author intended him to represent Order. This means that he contains the Problem element (the inappropriate attitude or approach that is the underlying source of the Story’s troubles), rather than the Solution Element, and as such must Change in order to succeed.

The entire first scene with Grant at the dig should have illustrated his love of Order. All the elements were there: a disruptive boy, a randomly sensitive computer, a helicopter that comes out of nowhere and ruins the dig. All of these things could have illustrated Grant’s hatred of Chaos and his quest for Order. Using the same events and incidents the point might have been made in any number of ways, the easiest being a simple comment by Dr. Grant himself.

Unfortunately without any direct allusion to Order being his primary concern, Dr. Grant comes off simply as finding disruptions inconvenient, faulty equipment annoying, and kids as both.

Why is it so important to set up the nature of the problem so early? Well, one of the major problems with the Jurassic Park storyform is that we really don’t know what the problem is until near the end of the first act. Certainly almost every movie goer must have been aware that this was a picture about an island where they cloned dinosaurs back to life, and they run amok wreaking havoc – that’s all storytelling. But that doesn’t say why. The “Why” is the storyform: the excuse, if you will, for having a story to tell. If the point of contention had been established up front, the whole thrust of the picture would have been given direction from scene one.

Just stating that Dr. Grant shares the problem with the story is obviously not enough. The relationship between his view of the problem and the Objective view of the problem is what explores the concept, makes the argument, and allows the Main Character to grow. Ultimately, it is the differential between the two that brings a Changing (versus Steadfast) Main Character to suspect the error of their ways and make a positive leap of faith. They see the problem outside themselves, then find it inside themselves. They change the inside, and the outside follows suit.

What does this mean for Jurassic Park? As it is, Doctor Grant’s attitude toward John Hammond’s ability to control the dinosaurs is one of skepticism, but not because of Order, because of Chaos. Grant simply agrees with Ian Malcolm, the mathematician. This makes the same point from two directions. But Grant’s function is not to tout Chaos, but to favor Order. Only this point of view would be consistent with his feelings toward the children.

As illustrated in the table scene with Hammond, Ian, and Elissa, Grant jumps from representing his original approach to representing the opposite, neutralizing his effectiveness as owner of the crucial element and taking the wind out of the dramatic sails.

This problem could have been easily avoided and strong drama created by having Dr. Grant continue to believe that the park is unsafe, but for different reasons.

(Note: The following proposed scene is designed to illustrate how Grant’s and Ian’s positions on what is needed for the park to be safe is different. The storytelling is minimal so as not to distract from the storyforming argument.

GRANT

How can you be sure your creations won’t escape?

HAMMOND

Each compound is completely encircled with electric fences.

GRANT

How many fences?

HAMMOND

Just one, but it is 10,000 volts.

GRANT

That’s not enough….

HAMMOND

I assure you, even a T-Rex respects 10,000 volts!

GRANT

No, I mean not enough fences. It’s been my experience that Dr. Malcom is right. You can’t count on things going the way you expect them. You need back-ups to your back-ups. Leave a soft spot and Chaos will find it. Put three fences around each compound, each with a separate power source and then you can bring people in here.

MALCOLM

That’s not the point at all! Chaos will happen no matter how much you prepare. In fact, the more you try to control a situation, the greater the potential that chaos will bring the whole thing down.

In the above scene, Grant stresses the need for even MORE control than Hammond used. This clearly establishes his aversion to giving in to chaos. But Ian illustrates the difference in their points of view by stating that the greater the control you exercise, the more you tighten the spring of chaos.

What would this mean for the middle of the story? Plenty. Once Grant and the children are lost in the open with the thunder lizards, he might learn gradually that one must allow Chaos to reach an equilibrium with Order. Several close encounters with the dinos might result in minor successes and failures determined by applying Order or allowing Chaos.

As it stands, Dr. Grant simply learns to care about the children. But what has really changed in him? What did he learn? Would it not have been more dramatically pleasing to have the children teach him how chaos is not just a disruptive element, but sometimes an essential component of life? And would it not make sense for someone who has spent his whole life imagining the way dinosaurs lived to be surprised by the truth when he sees them in person? What a wonderful opportunity to show how the Orderly interactions he had imagined for his beloved beasts are anything but orderly in the real world. So many opportunities to teach him the value of Chaos, yet all we get is “They DO travel in herds… I was right!” Well, that line is a nice place to start, especially if you spend the rest of the story showing how wrong he was about everything else. Truly a good place to start growing from.

Perhaps the most disappointing aspect of the Subjective Storyline is the manner in which they escape in the end. Grant and the kids are sealed in the control room, but the Raptors are right outside. The girl struggles to get the computer up so they can get the door locked. This of course, merely delays the Raptors until the helpless humans can escape into another Raptor attack. Then out of nowhere, T-Rex conveniently barges in, kills the Raptors and allows the humans to escape? Why? Why then? Was T-Rex just waiting in the wings for his cue?

Let’s describe one possible ending that would’ve tied in Chaos, Dr. Grant’s personal problem of order in the Subjective storyline, his growth as a character and eventual change, AND have all this force a successful outcome to the Objective storyline.

Imagine that earlier in the story, when the power went down it only affected some of the compounds, not all. So only some of the areas were open to the roving dinos. Rather than having Elissa get the power back on for the fences, she merely powers up the computer system, but then no one can boot it up.

Dr. Grant and the kids make it back to the control room, barely escaping the T-Rex who is trapped by one of the functional electric fences. They climb over the fence on a tree knocked down by the Tyrannosaurus. The Raptors are at the door of the control room, the girl goes to the computer to lock the door. She locks it, then tells Grant she can bring up the rest of the fences. There might be some kind of visual reminder in the room (such as a dino picture) that Grant (and the audience) associate with his major learning experience with the kids about needing to accept Chaos. Grant almost allows her to bring up the power, then yells for her to stop. He tells her not to bring it up, but to actually cut the power on all of the fences.

Just as before, the Raptors break in, the humans escape onto the dino skeletons. NOW, when T-Rex comes in to save the day, it is solely because of Dr. Grant’s decision to cut the power to the fence that was holding him in. Having learned his lesson about the benefits of Chaos and the folly of Order, he is a changed man. The author’s proof of this correct decision is their salvation courtesy of T-Rex.

Equilibrium is established on the island, Grant suddenly loves kids, he gets the girl, they escape with their lives, and all because the crucial element of Order connected both the Objective and Subjective storylines.

Certainly, Dramatica has many more suggestions for Building a Better Dinosaur, but, leapin’ lizards, don’t you think this is enough for one Constructive Criticism?

Try Dramatica Risk-Free for 90 Days!

Cool article and all, but you should try Dramatica for yourself. You can try it for 90 days risk-free. If you don’t like it after three months, just ask for a full refund. Simple as that, and definitely worth your time.

Click here for details or to purchase.

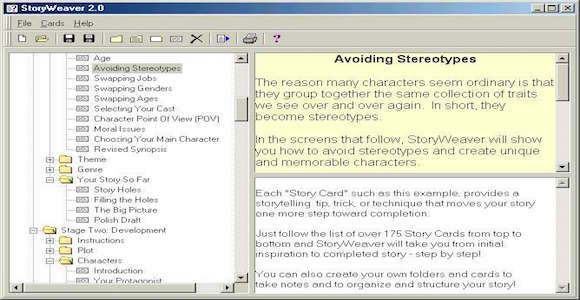

Try StoryWeaver Risk-Free for 90 Days Too!

If you’d rather spend a little more time on developing your story’s people before they become characters, its happenings before they become plot, the moral dilemmas before they become theme, and the personality of your story overall before it becomes genre, then try my entry-level StoryWeaver software, also risk-free for 90 days.

If you’d rather spend a little more time on developing your story’s people before they become characters, its happenings before they become plot, the moral dilemmas before they become theme, and the personality of your story overall before it becomes genre, then try my entry-level StoryWeaver software, also risk-free for 90 days.

Click here for details or to purchase.

Here’s a flashback article from the early days of the Dramatica theory of narrative structure back in the mid 1990s. It is the first article I wrote in a series of “Constructive Criticisms” in which I showed how Dramatica could have improved highly successful movies and books, not just ones that were obviously flawed.

Here’s a flashback article from the early days of the Dramatica theory of narrative structure back in the mid 1990s. It is the first article I wrote in a series of “Constructive Criticisms” in which I showed how Dramatica could have improved highly successful movies and books, not just ones that were obviously flawed.

The common expression “spinning a yarn” conjures up the image of a craftsperson pulling together a fluffy pile into a single unbroken thread. An appropriate analogy for the process of telling a tale. A tale is a simple, linear progression – a series of events and emotional experiences that leads from point A to point B, makes sense along the way, and leaves no gaps.

The common expression “spinning a yarn” conjures up the image of a craftsperson pulling together a fluffy pile into a single unbroken thread. An appropriate analogy for the process of telling a tale. A tale is a simple, linear progression – a series of events and emotional experiences that leads from point A to point B, makes sense along the way, and leaves no gaps. We all know that a story needs a sound structure. But no one reads a book or goes to a movie to enjoy a good structure. And no author writes because he or she is driven to create a great structure. Rather, audiences and authors come to opposite sides of a story because of their passions – the author driven to express his or hers, and the audience hoping to ignite its own.

We all know that a story needs a sound structure. But no one reads a book or goes to a movie to enjoy a good structure. And no author writes because he or she is driven to create a great structure. Rather, audiences and authors come to opposite sides of a story because of their passions – the author driven to express his or hers, and the audience hoping to ignite its own. The Protagonist is one of the most misunderstood characters in a story’s structure.

The Protagonist is one of the most misunderstood characters in a story’s structure.