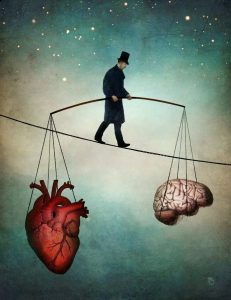

The common expression “spinning a yarn” conjures up the image of a craftsperson pulling together a fluffy pile into a single unbroken thread. An appropriate analogy for the process of telling a tale. A tale is a simple, linear progression – a series of events and emotional experiences that leads from point A to point B, makes sense along the way, and leaves no gaps.

A tale is, perhaps, the simplest form of storytelling structure. The keyword here is “structure.” Certainly, structure isn’t necessary to communicate powerful feelings as a montage of experiences. One can still relate a conglomeration of intermingled scenarios, each with its own meaning and emotional impact. Many well-known works of this ilk are considered classics, especially as novels or experimental films.

Nonetheless, if one wants to make a point, you need to create a line that leads from your premise to your conclusion. A tale, then, is a sequence of dramatic elements leading from the point of departure to the destination on a single path.

A story, on the other hand, is a more complex form of structure. Essentially, a number of different story threads are intertwined around one another, much as a artist might weave a tapestry. Each individual thread is a tale that needs to be spun, making its own internal message complete, unbroken, and possessing its own sequence. But collectively, the messages of all the threads come together in a single, overall pattern in the tapestry of the story, much as the scanning lines on a television come together to create the image of a single frame.

In story structure, then, the sequence of events in each individual thread cannot be random, but must be designed to do double-duty – both making sense as an unbroken progression and also as pieces of a greater purpose.

To be a story thread, a sequence of dramatic elements must have its own beginning, middle, and end. For example, every character’s growth has its own thread. Typically, this is referred to as a character arc, especially when in reference to the main character. But an “arc” has nothing to do with the growth of a character. Rather, each character’s emotional journey is a personal tale that describe his or her feelings at the beginning of the story, at every key juncture, and at the final reckoning.

Some characters may come to change their natures, others may grow in their resolve. But their mood swings, attitudes, and outlook must follow an unbroken path that is consistent with a series of emotions that a real human being might experience. For example, a person will not instantly snap from a deep depression into joyous elation without some intervening impact, be it unexpected news, a personal epiphany, or even the ingestion of great quantities of chocolate. In short, each character’s throughline must be true to itself, and also must take into consideration the effect of outside influences.

How can we use this throughline concept? Well, right off the bat, it helps us break even the most complex story structures down into a collection of much simpler elements. With the throughline concept, we can far more easily create a story structure, and can also ensure that every element is complete and that our story has no gaps or inconsistencies.

Traditionally, writers would haul out the old index cards (or their equivalent) and try to create a single sequential progression for their stories from Act I, Scene I to the climax and final denouement.

An unfortunate byproduct of this “single throughline” approach is that it tended to make stories far more simplistic than they actually needed to be since the author would think of the sequential structure as being essentially a simple tale, rather than a layered story.

In addition, by separating the throughlines it is far easier to see if there are any gaps in the chain. Using a single thread approach to a story runs the risk of having a powerful event in one throughline carry enough dramatic weight to pull the story along, masking missing pieces in other throughlines that never get filled. This, in fact, is part of what makes some stories seem disconnected from the real world, trite, or melodramatic.

By using throughlines it is far easier to create complex themes and layered messages. Many authors think of stories as having only one theme (if that). A theme is just a comparison between two human qualities to see which is better in the given situations of the story.

For example, a story might wish to deal with greed. But, greed by itself is just a topic. It doesn’t become a theme until you weigh it against its counterpoint, generosity, and then “prove” which is the better quality of spirit to possess by showing how they each fare over the course of the story. One story’s message might be that generosity is better, but another story might wish to put forth that in a particular circumstance, greed is actually better.

By seeing the exploration of greed as one throughline and the exploration of generosity as another, each can be presented in its own progression. In so doing, the author avoids directly comparing one to the other (as this leads to a ham-handed and preachy message), but instead can balance one against the other so that the evidence builds as to which is better, but you still allow the audience to come to its own conclusion, thereby involving them in the message and making it their own. Certainly, a more powerful approach.

Plot, too, is assisted by multiple throughlines. Subplots are often hard to create and hard to follow. By dealing with each independently and side by side, you can easily see how they interrelate and can spot and holes or inconsistencies.

Subplots usually revolve around different characters. By placing a character’s growth throughline alongside his or her subplot throughline, you can make sure their mental state is always reflective of their inner state, and that they are never called upon to act in a way that is inconsistent with their mood or attitude at the time.

There are many other advantages to the use of throughlines as well. So many, that the Dramatica theory (and software) incorporate throughlines into the whole approach. Years later, when I developed StoryWeaver at my own company, throughlines became an integral part of the step-by-step story development approach it offers.

How do you begin to use throughlines for your stories? The first step is to get yourself some index cards, either 3×5 or 5×7. As you develop your story, rather than simply lining them all up in order, you take each sequential element of your story and create its own independent series of cards showing every step along the way.

Identify each separate kind of throughline with a different color. For example, you could make character-related throughlines blue (or use blue ink, or a blue dot) and make plot related throughlines green. This way, when you assemble them all together into your overall story structure, you can tell at a glance which elements are which, and even get a sense of which points in your story are character heavy or plot or theme heavy.

Then, identify each throughline within a group by its own mark, such as the character’s name, or some catch-phrase that describes a particular sub-plot, such as, “Joe’s attempt to fool Sally (or more simply, the “Sally Caper.”). That way, even when you weave them all together into a single storyline, you can easily find and work with the components of any given throughline. Be sure also to number the cards in each throughline in sequence, so if you accidentally mix them up or decide to present them out of order for storytelling purposes, such as in a flashback or flash forward, you will know the order in which they actually need to occur in the “real time” of the story.

So, bottom line: you spin a tale or you can weave a story, but if you want to convey a complex message, you need to ensure that every thread is not only a quality one, but that they all work together to create a greater meaning.

This technique is the heart of our StoryWeaver Story Development Software. Click here for details or to try it risk-free for 90 days.

Melanie Anne Phillips

Creator, StoryWeaver