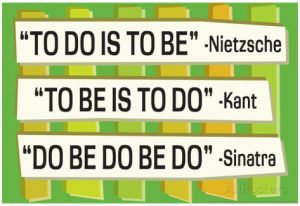

EXPLANATION: Some of the characters you create as an author will be Do-ers who try to accomplish their purposes through activities (by doing things). Other characters are Be-ers who try to accomplish their purposes by working it out internally (by being a certain way). When it comes to the Main Character, this choice of Do-er or Be-er will have a large impact on how he approaches the Story’s problem. If you want your Main Character to prefer to solve problems externally, choose Do-er. If you want your Main Character to prefer to solve problems through internal work, choose Be-er.

THEORY: By temperament, Main Characters (like each of us) have a preferential method of approaching Problems. Some would rather adapt their environment to themselves through action, others would rather adapt their environment to themselves through strength of character, charisma, and influence.

There is nothing intrinsically right or wrong with either Approach, yet it does affect how one will respond to Problems.

Choosing “Do-er” or “Be-er” does not prevent a Main Character from using either Approach, but merely defines the way he is likely to first Approach a Problem, using the other method only if the first one fails.

USAGE: Do-er and Be-er should not be confused with active and passive. If a Do-er is seen as active physically, a Be-er should be seen as active mentally. While the Do-er jumps in and tackles the problem by physical maneuverings, the Be-er jumps in and tackles the problem with mental deliberations.

The point is not which one is more motivated to hold his ground but how he tries to hold it.

A Do-er would build a business by the sweat of his brow.

A Be-er would build a business by attention to the needs of his clients.

Obviously both Approaches are important, but Main Characters, just like the real people they represent, will have a preference. Having a preference does not mean being less able in the other area.

A martial artist might choose to avoid conflict first as a Be-er character, yet be quite capable of beating the tar out of an opponent if avoiding conflict proved impossible.

Similarly, a school teacher might stress exercises and homework as a Do-er character, yet open his heart to a student who needs moral support.

When creating your Main Character, you may want someone who acts first and asks questions later, or you may prefer someone who avoids conflict if possible, then lays waste the opponent if they won’t compromise.

A Do-er deals in competition, a Be-er in collaboration.

The Main Character’s affect on the story is both one of rearranging the dramatic potentials of the story, and also one of reordering the sequence of dramatic events.

By choosing Do-er or Be-er you instruct Dramatica to establish one method as the Main Character’s approach and the other as the result of his efforts.

The primary colors enable you to create the whole range of shading and tonalities you are trying to achieve in a picture.

The primary colors enable you to create the whole range of shading and tonalities you are trying to achieve in a picture.