Here are six ways in which your Main Character can flirt with change over the course of your story, up to the climax where they will either embrace change or reject it, as Scrooge accepts change in A Christmas Carol while William Wallace remains resolute in Braveheart.

Here are six ways in which your Main Character can flirt with change over the course of your story, up to the climax where they will either embrace change or reject it, as Scrooge accepts change in A Christmas Carol while William Wallace remains resolute in Braveheart.

Let’s take a look at each of these six kinds of characters, and how they respond to pressures on their belief system, morality, attitude or personal code.

1. The Steady Freddy

This kind of Main Character starts out with a fixed belief about the central personal issue of the story. Act-by-Act, Scene-by-Scene, he gathers more information that leads him to question those pre-held beliefs. His hold on the old attitude gradually weakens until, at the Moment of Truth, he simply steps over to the other side – or not. This kind of character slowly changes until he is not committed to either his original belief or the alternative. It all comes down to which way the wind is blowing when he ultimately must choose one or the other.

2. The Griever

A Griever Main Character is also confronted with building evidence that his original belief may have been in error. But unlike Steady Freddy, this character suffers a growing internal conflict that starts to tear him apart. The Griever feels honor-bound or morally obligated to stick with his old loyalties, yet becomes more and more compelled to jump ship and adopt the new. At the end of the story, he must make a Leap of Faith, choosing either the old or the new, and with such a balance created, there is not even a hint as to which way would ultimately be better.

3. The Weaver

The Weaver Main Character starts out with one belief system, then shifts to adopt the alternative, then shifts back again, and again, and again…. Like a sine wave, he weaves back and forth every time he confronts information that indicates he is currently in error in his point of view. The intensity of these swings depends upon the magnitude of each bit of new information and the resoluteness of the character.

4. The Waffler

Unlike the Weaver, the Waffler jumps quickly from one point of view to the other, depending on the situation of the moment. He may be sincere but overly pragmatic, or he may be opportunistic and not hold either view with any real conviction. Still, in the end, he must come down on one side of the fence or the other.

There are also two kinds of characters who change, but not really.

5. The Exception Maker

This character reaches the critical point of the story and decides that although he will retain his original beliefs, he will make an exception “in this case.” This character would be a Change character if the story is about whether or not he will budge on the particular issue, especially since he has never made an exception before. But, if the story is about whether he has permanently altered his nature, then he would be seen as steadfast, because we know he will never make an exception again. With the Exception Maker, you must be very careful to let the audience know against what standard it should evaluate Change.

6. The Backslider

Similar to the Exception Maker, the Backslider changes at the critical moment, but then reverses himself and goes right back to his old belief system. In such a story, the character must be said to change, because it is the belief system itself that is being judged by the audience, once the moment of truth is past and the results of picking that system are seen in the denoument. In effect, the Backslider changes within the confines of the story structure, but then reverts to his old nature AFTER the structure in the closing storyTELLING.

An example of this occurs in the James Bond film, “On Her Majesty’s Secret Service.” This is the only Bond film in which 007 actually changes. Here, he has finally found love which has filled the hole in his heart that previously drove him. He resigns the force and gets married. End of structure. Then, in additional storytelling, his wife is killed by the villain, and his angst is restored so good ol’ James Bond can return just as he was in the next sequel.

Variations….

Each of these kinds of characters may be aware that he or she is flirting with change or may not. They may simply grieve over their situations, or just breeze through them, not considering how they might be affected. Each of these characters may arrive at a Leap of Faith where they must make a conscious decision to do things the same way or a different way, or each may arrive at a Non-Leap of Faith story conclusion, where they never even realize they have been changed, though they have been, gradually. The important thing is that the readers or audience must know if the Main Character has changed or not. Otherwise, they cannot make sense of the story’s message.

There are many ways to Change or Not to Change. If you avoid a linear path and a binary choice, your characters will come across as much more human and much more interesting.

Design your main character’s journey of growth

with StoryWeaver Story Development Software

StoryWeaver will take you step-by-step from concept to fully developed story. More than 200 interactive Story Cards (TM) guide you through each step and automatically reference your work on previous steps. So, your story is constantly evolving as you revise, refine, and fold each version into the next.

StoryWeaver will take you step-by-step from concept to fully developed story. More than 200 interactive Story Cards (TM) guide you through each step and automatically reference your work on previous steps. So, your story is constantly evolving as you revise, refine, and fold each version into the next.

With our 90 day money-back guarantee you can try StoryWeaver risk-free.

And, even if you choose not to keep it, you still get to keep our Writer’s Survival Kit Bonus Package!

Your main character doesn’t have to change in order to grow; they can grow in their resolve not to change. Some characters, like Scrooge in A Christmas Carol or Rick in Casablanca , do change, while others, like Rocky in Rocky or William Wallace in Braveheart, hold onto their beliefs.

Your main character doesn’t have to change in order to grow; they can grow in their resolve not to change. Some characters, like Scrooge in A Christmas Carol or Rick in Casablanca , do change, while others, like Rocky in Rocky or William Wallace in Braveheart, hold onto their beliefs. There are two story lines in every complete story, and you can either run them in parallel or you can hinge them together to form a dramatic triangle.

There are two story lines in every complete story, and you can either run them in parallel or you can hinge them together to form a dramatic triangle.

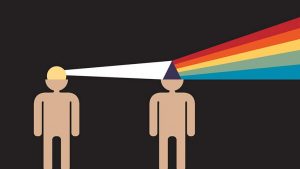

What is an Influence Character? First, let’s look at some wide-ranging examples of Influence Characters in well-known stories to show their use and effect, then a bit about how to put one in your story.

What is an Influence Character? First, let’s look at some wide-ranging examples of Influence Characters in well-known stories to show their use and effect, then a bit about how to put one in your story. Perhaps the best way to instill real feelings in a character is to stand in his or her shoes and write from the character’s point of view. Unfortunately, this method also holds the greatest danger of undermining the meaning of a story.

Perhaps the best way to instill real feelings in a character is to stand in his or her shoes and write from the character’s point of view. Unfortunately, this method also holds the greatest danger of undermining the meaning of a story.

Some stories introduce characters as people and then let the reader/audience discover their roles and relationships afterward. This tends to help an audience identify with the characters.

Some stories introduce characters as people and then let the reader/audience discover their roles and relationships afterward. This tends to help an audience identify with the characters.

Over the course of the story, your reader/audience has come to know your characters and to feel for them. The story doesn’t end when your characters and their relationships reach a climax. Rather, the reader/audience will want to know the aftermath – how it turned out for each character and each relationship. In addition, the audience needs a little time to say goodbye – to let the character walk off into the sunset or to mourn for them before the story ends.

Over the course of the story, your reader/audience has come to know your characters and to feel for them. The story doesn’t end when your characters and their relationships reach a climax. Rather, the reader/audience will want to know the aftermath – how it turned out for each character and each relationship. In addition, the audience needs a little time to say goodbye – to let the character walk off into the sunset or to mourn for them before the story ends. All too often in stories, relationships and interchanges between characters of different sexes come off stilted, unbelievable, or contrived. In fact, since the author is writing from the perspective of only one of the two sexes, characters of the opposite sex often play more as one sex’s view of the opposite sex, rather than as truly being a character OF the opposite sex. This is because the author is looking AT the opposite sex, not FROM its point of view.

All too often in stories, relationships and interchanges between characters of different sexes come off stilted, unbelievable, or contrived. In fact, since the author is writing from the perspective of only one of the two sexes, characters of the opposite sex often play more as one sex’s view of the opposite sex, rather than as truly being a character OF the opposite sex. This is because the author is looking AT the opposite sex, not FROM its point of view.

Although a personal goal for each character is not absolutely essential, at some point your readers or audience is going to wonder what is driving each character to brave the trials and obstacles. If you haven’t supplied a believable motivation, it will stand out as a story hole.

Although a personal goal for each character is not absolutely essential, at some point your readers or audience is going to wonder what is driving each character to brave the trials and obstacles. If you haven’t supplied a believable motivation, it will stand out as a story hole.