We all have certain fundamental broad-stroke mental traits such as Reason, Initiative, and Skepticism. As individuals, we use the full spectrum of these tools to try and solve our problems. But when we get together in groups, we quickly self-organize so that one person emerges as the Voice of Reason for the group, another as the Goal-Oriented Leader, and another as the Resident Skeptic.

We specialize in this manner because when trying to solve a group problem or advance a group agenda, we are far more productive together is we each focus on just one of these fundamental tools rather than being a collection of general practitioners all trying to do all the jobs. In this manner, the group gets far greater thought, depth, and action in each area, and then we come together to share with the group what we have found in our area – to say, “this is what it looks like from here.”

In short, the group becomes a model of the individual mind, since that is exactly what we do as individuals, but now each of our attributes has become an archetypal role in a group narrative.

And that is where archetypes really come from – not the collective unconscious per se, nor from myth nor dreams, but simply from the attributes that are common to us all.

So in a sense, the narrative of an individual, and the narrative of a group are the same system at work at two different fractal dimensions.

And each of these has identical structural elements and dynamics.

And yet, the purposes of the group, though shared by each individual in the group, may sometimes come into conflict with a given member’s individual purposes. In fact, all the conflict and tension that is generated in stories and in life come from the dissonance between the needs of the individual and the needs of the group.

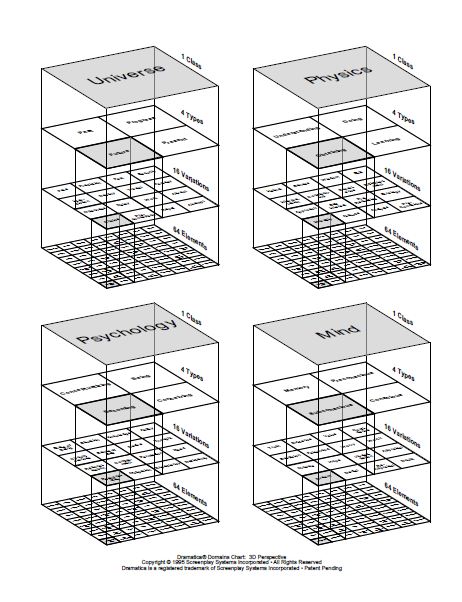

The Dramatica model presents this elegantly. The structural model you see can be the mind of one person or the collective mind of a group. It is the same structure, interpreted in two different ways.

When we look at the four levels of the structure as if it were a group mind, we see (from the bottom up) motivations, evaluations, methods, and purposes. When we look at the same four levels as a group mind we see Characters, Theme, Plot and Genre.

The Dramatica twists and turns like a Rubik’s cube, but not arbitrarily. Rather, there are two “justification wind-ups” – essentially two sets of dynamics that torque the structure, twisting it into a position that best fits that mind to its environment. One of these is the Main Character wind-up – representing the compromises he or she has had to make in their outlook to get by in the world and the other is the Objective Story wind-up, which represents the compromises a group mind has had to make to survive. In fact, it is these compromises that determine personality – all the attractions and repulsions based on our unbalanced minds.

And so, to truly understand one’s personal narrative, one must become aware of how the naturally balanced and neutral mind that exist only conceptually differs from the dynamic tensions that are self-perpetuating within ourselves.

In real life we have hundreds of narratives in which we participate, sometimes as the main character and sometimes as one of the archetypes in a larger group mind.

In the end, as complex as this view of the mind is, it all boils down to the fact that once you learn about the equations that generate Dramatica’s quads and the dynamic algorithms that drive the justification wind-ups, you lose the ability to lie to yourself. You can still choose to lie to others, of course, and you can still do terrible things to others, but you will no longer be able to see it as good in your own mind.

To know Dramatica at the core of its representation of human psychology is see the real reasons for your actions and attitudes, whether you want to or not. And I suppose that is the most accurate form of self-knowledge we are allowed in this world.

Melanie Anne Phillips

Co-creator, Dramatica